|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects

Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania :: Portland, Oregon |

Navigation ::

Home ::

Grindstone

Navigation ::

Home ::

Grindstone

Ye Older Grindstones

6/25/2006

|

Metal label

Keepsake box by Ralph C. Pelton

White cuban mahogany

Circa 1914 |

This

keepsake box was a companion piece made by Pelton to go with the floor

lamp he produced for Lake Place. The image of the whole may be seen

here. |

Passageway, 2.

Continuing with the Purcell

"autobiography" keystrokes for William Gray

Purcell, Part III (it will be up in the next day or so) of the "Preliminary

Draft on 'P & E' Thesis," I confess that I have inadvertently done an injustice

with the illustrations. The ones appearing with the Grind previous should

really have been put here. I just got a little ahead of the narrative

discourse. I shall compensate by wandering father afield in the scope of

my comments and thereby increasing my opportunities for visual tesserae.

Mosaic is just another word for the big picture.

Terra-cotta finial

Farmers National Bank

Owatonna, Minnesota 1905

Photograph by Tom Shearer |

A

word aside, before we go there. Over the next four

installments of the manuscript, Purcell presents the seed time two years of his apprenticeship period

in the West, landing in Berkeley in 1904 after a brief exploratory job

search in Los Angeles with Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey, both of whom knew

him from membership in the Chicago Architectural Club. He then made

his way further north to Seattle where, in all likelihood, he got

infected with the tuberculosis that would finally emerge in 1928 to

burden the last three and a half decades of his life. The West Coast

apprenticeship period ends with the insistent offer from Charles A.

Purcell for his son to take a year long trip to Europe.

In one of the two documented moments

of prescience by the elder Purcell, he asked his son to abandon the

Pacific northwest because of his fear that WGP would be exposed to

tuberculosis! The other eye-catching piece of precognition is found in

his last mailed letter to his son, which he signs "So long, Pa,"

instead of the regular closing which he had used consistently

throughout all his previous correspondence with WGP over the years.

William Purcell, of course, caught this right away and annotated the

letter with his amazement, since his father's death was not

anticipated.

Purcell is candid about a failed

marriage engagement but the reasons for the breakup with the young

lady, who had his ring on her finger for about two days, were

amorphous even some fifty years later. A lot of different spin can be

put on the phrase "It began to seem as it we were not going to make it

as a married pair." Purcell goes on to list this as one of several

motivations for leaving his chair in the workless Sullivan's office

and heading to Los Angeles to fulfill his long held "westering urge." |

Frank Lloyd Wright being arrested in

Minnesota |

The other personal circumstance hinted at by Purcell as a reason to

depart Oak Park can be better detailed. His father and his mother were

entering the end game of a marriage that had not worked from the

beginning. As people of privilege and high social standing, divorce

was a bad fruit that could only be held in check as a very last

resort. The example of Frank Lloyd Wright in leaving his wife had yet

to rock the conservative prairie community, a scandal that would

continue to dog his steps for another thirty years. The long memories

of those shocked and awed by Wright's disgraceful behavior were

undoubtedly stirred to smugness when he was finally arrested

downstream in the transition period between Miriam and Olgivanna. |

But none of that had yet happened when

the marriage between Charles and Anna Gray Purcell was finally about to

explode. Anna Purcell was never interested in motherhood and left the

raising of her sons, William and his brother Ralph, to her own mother

Catherine Garns Gray. While Charles Purcell was quite wealthy, a

millionaire from being the arbiter of grain quality at the Chicago Board

of Trade and owner of various milling companies, he was a conservative man

who preferred a private, low-key lifestyle. Anna, however, loved the

pleasures of traveling and salon society. The two were ill-suited

companions in life but it took twenty-five years for the clock to run out.

Run out it did, right at the end of the apprenticeship period for Purcell.

| The ax would not truly

fall until 1906, when Anna vehemently demanded her luggage from the

ruins of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco right after the earth

stopped shaking but before the fire began. William Gray Purcell was

already in Europe when Anna rocketed into Los Angeles as an earthquake

survivor and crashed down at with her husband's aunts in the same

house where Purcell had stayed two years earlier while interviewing

for work with Myron Hunt. For some reason, she started at that moment

giving vicious newspaper interviews to cure the public of any high

regard for her deceased father, W. C. Gray. The stories carried back

to Chicago by newswire, where her stunned mother Catherine was

accosted by reporters banging on her respectable Oak Park door. Being

the widow of a distinguished newspaper editor and a woman whose body

language never swayed from the upright, she sat exposed to an

unaccustomed side of the press. Her cross to bear, she wrote in a

letter, was that she could not "condone the iniquities of my children"

(we may perchance consider said iniquities of the children of W. C.

and Catherine Gray, son Frank and daughter Anna both, in a sooner

rather than later Grind). |

Palace Hotel

San Francisco, California

1906, post earthquake and fire |

"Bellman! I'm

checking out!"

--Anna Purcell |

The Purcell aunts, naturally, were

reduced to stone cold embarrassment and encouraged strongly the immediate

departure of their houseguest. Anna returned to Chicago, where no private

doors opened to her and she wound up staying in a Loop hotel. More

pestilential interviews hissed forth, even though Everett Sisson, Dr.

Gray's successor at his old newspaper The Interior, tried hard to

get the local gossip mongering stringers to let the pseudo-story die. The

whole time William Purcell, in Europe, was bombarded with time-delayed

letters from both his mother and grandmother. Even though everything that

was going to go badly had already happened by the time he got word via

mail steamer weeks later, at least he had the good luck to be out of the

country--something he noted himself. Charles A. Purcell was not so

fortunate. He finally paid Anna $50,000 to grant a divorce on the

condition she never opened her mouth again publicly. She ended her life

with suicide in 1914, back in Los Angeles, after being diagnosed with

breast cancer.

In this history we see a pattern of

behaviors in female family relationships that informed the role of women

in Purcell's life experience. The next instance in the cycle is Edna Summy,

WGP's first wife whose active lesbian relationships while staying at the

Purcell

summer residence in the artist

enclave of Rose Valley, Pennsylvania, attracted awkward questions from

adopted sons Douglas and James. As with the breakup between his mother and

his father, the rancor of the 1920s between WGP and Edna terminated in

abrupt separation. Purcell fled to a series of tuberculosis sanatoriums

and was obliged to dip deeply into his pockets to get a final break with

Edna. Fortunately yet sadly, Purcell's pockets happened right then to be

the deepest that they would ever be.

| His father, Charles,

died in 1931, and Purcell inherited the bulk of his father's holdings

in the form of a trust management that he immediately sought to have

removed. Charles A.

Purcell, the records indicate, felt his wealth was most secure in gold

bars. Although he didn't keep any laying around or stashed a vault, he

rather neatly owned title to several million dollars worth, but nary a

single share of stock. This, together with a

large acreage of land in North Dakota later sold back to the

government for pennies on the dollar, the

second River Forest house Purcell

had designed for his father in 1927, and such business interests as

were still active with long-time partner

Henry Einfeldt

for whom P&E did a house,

banked Purcell neatly against the onslaught of the Depression. And, of

course, in the democratic example of William Gray Purcell that meant a

large number of friends, colleagues, and even some total strangers

were also protected. You can about this period in greater detail in

the Guide essay, Banning, 1930-1935. |

Charles A. Purcell

residence #2

River Forest, Illinois 1927

|

Venue for

"Purcell and Elmslie" exhibition of 1953

Walker Art Center

Minneapolis, Minnesota |

|

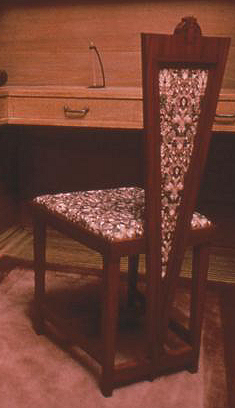

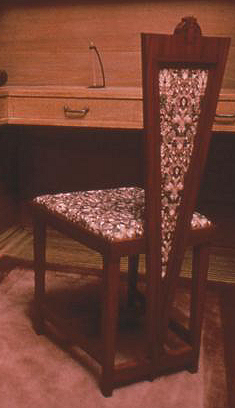

"Surprise point"

chair

Edna S. Purcell Residence

also known as Lake Place

Purcell and Elmslie

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1913

This chair is the one acquired from Edna

Purcell by WGP in 1953 for the Walker Center exhibition. Although part

of the William Gray Purcell Papers collection, the chair is now on

loan to the Minneapolis Institute of Art and is displayed in the place

it was originally created for in the Lake Place writing nook.

Ignore the current fabric covering

the seat and back. Purcell selected a bright, almost lime green silk

for the exhibition covering, and there is evidence that the original

silk covering was light blue. One of a pair, the other chair is still

westering in -- guess -- San Francisco! |

So, like Anna Catherine Gray Purcell in

her own time, was Edna. This sounds, I think, racier than it really was to

those having the experience. The shearing of divorce is likely unpleasant

under the best of circumstances. Purcell's was complicated by

simultaneously inheriting a huge fortune, being prone on a hospital bed

with physical exhaustion, and having to conduct the whole transaction

largely through the mail. Although expensive, the parting between Edna and

WGP was vastly more civil that than that of his parents, so much so that

twenty years later Purcell could call and borrow back one of the surprise

point chairs from Lake Place for the Walker Center

exhibition in 1953. Edna came to rest amidst the artistic shade of

Santa Barbara, where she died in 1959 of breast cancer. On balance, I

actually like Edna for some reason, though tangible traces of her such as

letters and photographs are slim pickings. Her actual presence to us is

sort of like the remains of original stencil patterns on the walls of so

many P&E houses; there aren't many even though we know they were once

there. For lack of evidentiary detail, Edna is destined to remain blurry

in our knowledge, almost dreamlike.

The most awakening photograph, although

it has been seen before in a Grind, we have is

a Lumière autochrome taken on a trip in 1915 to the Sequoias. Here

in this color image stand Catherine Garns Gray and Edna Summy Purcell,

their torsos turned indirectly and backs arched stiffly as they are

forced to stand too close to one another for the sake of a camera. I have

come to believe that the poet in Purcell could not have missed the

metaphor framed in his photograph. The axis mundi in the form of a massive

tree that supports the heavens arises in the background of women who

spurned each other enough to require two houses separated by an alley in

Minneapolis. The image whispers of forced cordiality for the sake of the

man for whom they favored a pose on vacation and who was relatively

speaking their own axis in life. Unless there are family albums yet to

come to archival light, this physical proximity was a rare photographic

occasion. The ghost of Anna Catherine, just dead by her own hand, is also

there, most likely standing right between them. Both Catherine Gray and

Charles A. Purcell, who vented his strong opinion loudly in front of young

teenager James Purcell during a confrontation with Edna one evening in the

Portland house, considered the life of their child William had been

debased, ruined bluntly put, by the presence of this woman. What else

could James do, under the circumstances, but internalize the hostility for

later application?

James, William, and Ann Purcell

Circa 1960 |

We can venture into

these streams of family relationships and sexual orientation easily

enough from Purcell's diaries, though that is one-sided, and perhaps

there is even worthwhile psychological reason to do so. He's a fair

man and a consistently reliable witness in his written traces in

general. There's no reason to doubt that the same character was at

work in records of more intimate family events. We don't have a

fraction of the detail from anyone else's point of view, however, save

an interview I did over the telephone with James Purcell in 1981. He

recollected to me his childhood in the 1920s living in Portland,

Oregon, talking to me about Edna and confirming her girlfriends with

some shock that I could have even known about that. He had a history

of antagonized relations with WGP, partly over money but much more

about hard feelings over the divorce, that resulted in a long period

of complete break. Jame's wife Ann (Purcell's mother's name minus one

letter) worked to reconcile the two men. They eventually did patch

things up to a certain degree in the early 1960s after Edna died, an

effect that did not take deep roots because the nurturing Ann would

herself pass away unexpectedly just after working the miracle of a

family reunion at Westwinds. |

As I noted in an earlier Grind, James Purcell related to me a history

of loud arguments over money between his parents. In running her household

Edna was beset with uncertain means to maintain a cook or a maid, while

Purcell continued blithely to indulge his expensive penchant for the

latest advances in photography. The situation grew ever worse because of

repeated bad investments made by Purcell with large sums of money, then

having to turn to the same man who had warned WGP not to undertake these

flaky financial speculations in the first place, his father, to be saved

from ruin. Even though there was a modest amount of work in his

architectural office, the Portland era was made possible almost purely by

burning capital. True, that same effect had been in play as the sheaves of

grain converted by Charles Purcell to gold bars came to pay for the early

and late years of the Purcell & Elmslie office. The difference was that

the firm had at least made some money during the good years from 1910 to

1914, especially from the work done for Charles R. Crane and Henry Babson.

For all the good art and architecture that sprang from his efforts, there

was no profit for Purcell in Portland, just loss upon loss.

By following a young man's urge to go

west in pursuit of his profession during his apprentice years, Purcell

spent two years exploring not just construction and the operations of

architectural offices but also surveying the landscape within which the

vast majority of his life would play out. Starting from touchdown in Los

Angeles, he covered the ocean front. Berkeley and San Francisco would be

back briefly in 1915 with building of the

Margaret Little residence

on Shattuck Avenue and the opening of the

Edison Shop on

Union Square. Seattle was only a toe in the water in 1906, a place to

which he didn't return except perhaps incidentally. Portland was the

middle point where he alighted with renewed hope in late 1919 but

descended slowly thereafter into the iron lung grasp of tuberculosis.

Swinging south into the desert to lay on his back for four years, 1931 to

1935, in Banning, California, Purcell got his divorce, re-married to

second wife Cecily (whose weakened physical condition from emphysema like

his own from TB enabled a purely platonic relationship), and closed out

the last thirty years at Westwinds, on the top of a low foothill in

Monrovia. A West Coast life indeed,

for a man whose greatest fame centers in the heart of the continental

prairies where he was born. Somehow, there is a kind of karmic jujitsu at

work there.

Next up:

William Gray Purcell, Part IV |

6/18/2006

| |

|

Passageway.

With this Grind we commence a

faithful journey that will take some weeks to complete. As noted earlier,

Purcell wrote a group of essays that were in effect his autobiography.

Ironically, I am at the moment absent the very first page, which has

become inadvertently separated from the binder containing my ancient

photocopy. I am in the process of looking for Page One of One, but rather

than delay progress I have keyed in William

Gray Purcell, Part II. This covers the period of

his apprenticeship, including an account of his first jobs after

graduating from Cornell and the very beginning of his relationship with

Elmslie in the development of the "Village Library" competition entry for

The Brickbuilder. I

considered illustrating the narrative, something that Purcell did

frequently in preparing manuscripts for others and especially after he

bought his photocopy machine in 1960. I have not done so, even though it

would be easy to choose the standard icons. This particular manuscript has

a very different background than the "presentation books" in which

portions of the essays sometimes appear. In the early 1950s Purcell became

involved with David S. Gebhard, an architectural historian wanting to do

his doctoral dissertation on Purcell & Elmslie. Purcell opened his

archives to Gebhard, providing complete access to the historical record of

the firm. This manuscript was another product of that involvement.

<Comment deleted - I'm not going

there>

For Purcell, this was an opportunity to

ensure lasting scholarly validation of the contribution by P&E to American

architecture, one only partly about his own participation. Purcell

developed numerous extensive accounts of various people, commissions,

events, and background circumstances to make sure a fully informed picture

emerged in the dissertation. In addition to the earlier

Parabiographies

manuscripts, which were reviewed and further revised in this process,

he also generated several hundred pages of formally organized,

double-spaced typewritten pages, portions of which were produced in the

third person, that were given to Gebhard. These pages were organized by

section into the various periods of his life and practice up to the

dissolution of P&E in 1921.

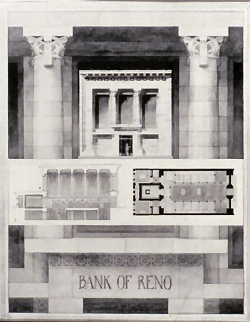

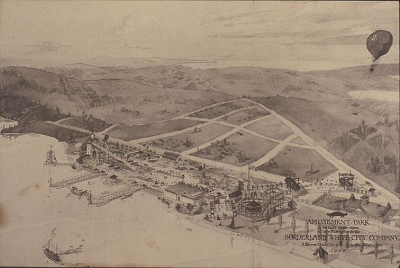

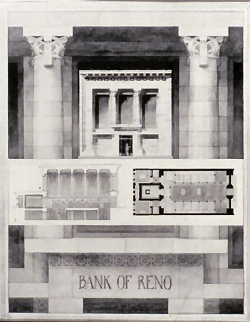

Design for a City Bank

"Bank of Reno"

Illustrated in Chicago Architectural Club Catalog (#18, 1905, plate

18)

William Gray Purcell |

Subsequent to the award

of his doctorate, Gebhard took the normal course and sent his thesis

to numerous academic publishers to monumentalize the work as a book.

All of them declined the manuscript. After his many efforts, Purcell

was keenly disappointed and mounted a campaign to reconfigure and get

published what was called "The Book." One result was the "Preliminary

Draft on 'P & E' Thesis" by Purcell, and that manuscript evolved

from 1955 to 1957 as a form of autobiography. The web structure for

this manuscript has already been created. We now press forward into

the individual sections as the fingertips permit. |

One of the things that jumps right out in

the current chapter is how Purcell honored those who brought value to both

his professional and personal experience, an obvious expression of his

democratic character. His accounts of architect F. W. Fitzpatrick and

The Brickbuilder publisher Arthur D. Rogers are typical of those found

throughout his many writings. Some of the people Purcell mentions remained

in friendly touch with him for many years, an indication of the lasting

good impression made by Purcell. In other instances, Purcell's kind

recollection may be the only record left on earth. Indeed, one of the more

valuable but lesser known attributes of the treasury formed by the William

Gray Purcell Papers is the continued remembrance of "ordinary" but

productive people who have otherwise vanished, as Purcell put it elsewhere

in this manuscript, "now passed from recorded life like a summer rain"

[WGP Review of [David S.] Gebhard Thesis, Purcell and Elmslie III,

Section B, John Jager and other personalities" (draft dated 2 April 1956)].

This chapter also includes recollection

of Lawton S. Parker, an artist who is hardly

likely to be forgotten until the Impressionists are no more. Parker has

been mentioned

in the Grind before as a prodigy discovered by Purcell's grandfather.

Aside from his impact as an older "big brother" who, this manuscript

reveals, started Purcell out on his very first architectural drawing,

Parker's painting of W. C. Gray made for the World's Columbian Exposition

is now permanently installed in Lake Place, and a second portrait done in

1894 that descended to the Purcell collection as a treasured family

heirloom.

Because of the time required to key these

pages, the amount of illustrative material will be somewhat reduced until

the text is in place. The copy I have is too poor to be OCR'd. Some links

are obvious and can be made right away, but the manuscript suggests

additional content for areas of the site that have remained heretofore

underdeveloped.

|

|

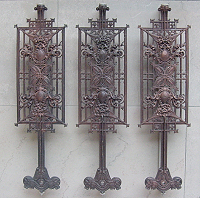

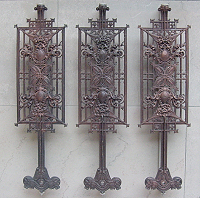

Ornamental details

R.W. Sears

Building

George Nimmons, Architect

Chicago, Illinois 1911 |

|

Other notes: The Case of the

Mystery Guest has been solved! The last Grind asked readers to identify a

small commercial building in Chicago near the Monadnock Building with some

creditable "Sullivanesque" terra-cotta enrichment. Thanks to John Panning

and Phil Pecord for letting us know that the building was done by George

Nimmons.

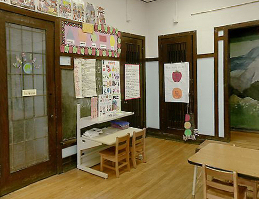

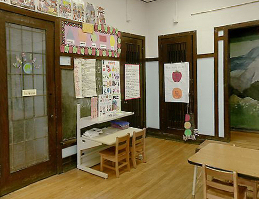

Helen C. Pierce Public School,

kindergarten alterations

Chicago, Illinois 1918 |

Helen C. Pierce Public School,

kindergarten alterations

Chicago, Illinois 1918 |

New pages have been added for the

Charles O. Alexander summer residence, alterations

(Squam Lake, New Hampshire 1919) and the Helen C. Pierce

Public School, kindergarten alterations (Chicago, Illinois 1918). The

linked Quicktime virtual reality movie for the kindergarten is a neat

treat available from the Chicago Institute of Art web site, but alas only

six of the eleven Norton panels are visible.

|

|

Next up:

William Gray Purcell - Part III.

|

6/3/2006

Capitals from upper sales floors

Schlesinger and Mayer Dry Goods Store

later Carson, Pirie, Scott

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

Chicago, Illinois |

|

| |

daedal

\DEE-duhl\, adjective:

1. Complex or ingenious in form or

function; intricate.

2. Skillful; artistic; ingenious.

3. Rich; adorned with many things. |

|

Daedal-dee and Daedal-dumb.

Being the progenitors of what now passes for the English language, the

Brits are still leaders in the cultivation of heritage varieties of

words whereas in America descriptive ability is continually diminished

by monoculture, currently into a patois of acronyms suitable for the

keypads of telephones. U2, Brutus? Out of the name of an inventive

artistic genius from classical yore, albeit one reported to have killed his

nephew for showing signs of competitive cleverness, comes the perfect adjective

for many of the images currently before my eyes. True, there all the literary

permutations like daedalic, daedalian, and so forth, but at bottom

the word comes from the Greek daidallein meaning "to work artfully." I

have now found my seed word to describe Elmslie's decorative designs,

particularly those from his fifteen years with Sullivan. I have no record of

Elmslie having killed any of his sibling's children, however; we'll settle for a

fit of poetic license. |

|

|

|

Stair decoration

Bayard (later Condict) Building

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant

Elmslie, associated architect

New York, New York |

Terra-cotta panel

Unknown building

George Grant Elmslie 1905 |

Stair balusters

Schlesinger and Mayer Dry Goods Store

later Carson, Pirie, Scott

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

Chicago, Illinois

|

Frieze panel

Schlesinger and Mayer Dry Goods Store

later Carson, Pirie, Scott

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

Chicago, Illinois

|

|

A

visit to Chicago last year, my first with a digital camera, saw me

homeward to California with upwards of a thousand images--some of which

are better than others. Someone should write an article about the effects

of casual and virtually no expense digital shooting on photography; seems

sometimes like a triumph of quantity over quality in the tried and true

American way. I know I am less careful when there is no film to "waste,"

and my focus is therefore not as reliable as was formerly the case. I was

happy to visit the usual suspects in Oak Park and River Forest, including

my first foray inside the FLLW Home and Studio, Unity Temple, and the Robie house, a sweet side discovery -- see mystery guest, below -- while making homage to the Monadnock

Building, and a comfortable stay in the former Reliance Building, which is now the

Burnham Hotel.

Capital, main entrance vestibule

Schlesinger and Mayer Dry Goods Store

later Carson, Pirie, Scott

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

Chicago, Illinois |

Nearly ten years had passed since my previous visit to

Chicago proper, and save for one brief couple of hours one afternoon

spent in Oak Park while en route to my summer campus duties at

Taliesin in 2000; nearly twenty years had elapsed since I had seen

some of the P&E houses. The occasion of this recent trip was to be the

in-line guide for UCLA design students on their initiatory tour of

Prairie School/Progressive architecture.

I learned a great deal watching them meet places like the Auditorium

Building or the Carson, Pirie, Scott store for the first time. A few

were so entranced by various sites that they forgot to take pictures,

which is saying something good I trust.

Photographs are being added and links will be up

shortly:

- Schlesinger & Mayer Dry Goods Store

-

- Auditorium Building (making a debut here)

-

- Charles A. Purcell residence #1 (River Forest)

-

- Gage Building

-

|

Capital, first floor sales room

Bayard (later Condict) Building

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

New York, New York |

The trip to New York was

made all the more thrilling by fulfillment of my unshakable

determination to see the Bayard/Condict Building, Sullivan's only

"skyscraper" (13 stories) in the city. The effort coincided with my

first trip, and at that alone, on the famed New York City subway. Walking

the block from the Waldorf=Astoria to the platform where I caught the

6 train downtown, I had in hand instructions from the concierge to get

off one station later than I did. When the train announcer said, "Bleeker

Street," that was all I needed to step out bravely -- heaven knew

where -- in New York and hope to find the building. I needn't have

worried, as there it was, the very first thing to be seen coming up

the stairs from the subway station. I lucked

out completely, as the building was still undergoing restoration,

first floor doors were open, and the super was a friendly guy who told

me what they had found, what they had done, and what the general story

was on the salvation of the space. Locks tumbled and doors opened, and

even the hidden grottoes of the basement yielded moments of fine

treasure. |

|

One thing to

be seen was the new lobby design, for which had been dislodged the

terra-cotta frieze that formerly embraced the space and now was sunk

bodily, like wallpaper, to the wall behind the security desk by the

front door. There were a few of these panels in excess, now loose,

apparently, in the process of finding new lives beyond the building;

so some may turn up at auction, no doubt, eventually. The same design

of these frieze panels appears tucked beneath the eaves of the

building on the thirteenth floor. |

Lobby frieze panels displayed as wall grouping

Bayard (later Condict) Building

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

New York, New York |

Lobby skylight |

Front entrance

Bayard (later Condict) Building

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

New York, New York |

Upper stories, front

Bayard (later Condict) Building

Louis Sullivan, architect; George Grant Elmslie, associated architect

New York, New York |

Our mystery guest:

The following shots were taken from

street level at 19 W. Jackson Street in Chicago, summer of 2005. I could

see no indication of this building being recognized as a landmark, nor

since it was Sunday was the building open. However, the facade is a

mishmash of interesting "Sullivanesque" ornament.

Research on the internet has not yielded any information about the

architect or the date of construction. Knowing that those who read this

blog are often in the wise, I wonder if anyone knows who did this

building? Currently it seems host to a variety of professional offices,

including those of lawyers and architects. |

Which coat of paint came first, I wonder?

Was the original polychromed? |

|

|

Tech note: Mobile content providers rustle with stalled

discontent in the chute now, ready to find a price for positioning

movies and television shows on your cell phone screen. Yeah, right.

Aside from the ludicrous thought of the tiny real estate available to

the eyeball -- you want widescreen with that? -- there is the small

issue of the battery life. And I suppose the annoyance of an incoming

call right when the movie gets to the most important part. Clearly,

the notion of mobile content is another American expression of having

a hammer so everything is, therefore, a nail. Thus has it always, or

very nearly always, been in American architecture of any sort.

Next up:

Once and future autobiography, chapter the second |

research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons

![]() research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons