|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

10/5/2003

Business card for Louise Elmslie

Mural sketch for Lake Place, by Miles Sater

Original sketch for Lake Place mural, by Charles Livingston BullAll In The Family. One of the basic points overlooked by many architects and the historians who sweep up after them is that buildings are meaningless without reference to the people who create them. The life of the human beings involved sets the conditions, delivers the impetus, provides the resources, and gives purpose to architecture, not the other way around. So many architects and architectural writers seem to speak as if there is some god-like quality in architectural theory that endows design with virtue, rather than design being a mirror of the virtue already present in the lives of those whom a structure is intended to serve.

If anything, the architecture of the latter decades of the 20th century could be summarized as the Architecture of Assimilation. Human life was dissociated from the design process by the exaltation of abstract rationalizations that were, in the end, the overweening conceits of a very few people and the horde of collegiate sheep who followed them into the wasteland. The Borg have nothing on American architecture of the past sixty years. Progressive architecture, on the other hand, starts out with the notion that everyone involved contributes to the life of a building. The web of human relationships, needs, wants, and aspirations (that spiritual thing, again) concatenate to find tangible as well as intangible expressions in a whole process of living of which the building is a crystallization. Community was key.

One under reported aspect of that background is the way that the family members of Progressive architects contributed, something often less documented than the primary design process. Here are a few morsels. One of Elmslie's sisters, Louise, had a small cottage industry of embroidering textiles with the designs of her brother. He created her a business card. Walter Burley Griffin's brother-in-law Miles Sater did a sketch for the Lake Place fireplace over mantle before Purcell hired Charles Livingston Bull.

Speaking of murals, the original sketch by Bull for the Lake Place over mantle was cut and mounted by Purcell on two 8 x 11 boards. Herewith they are virtually rejoined, even though there is a little color variation that shows the seam. And lastly, a fireplace over mantle sketch by John W. Norton for Purcell's in-laws, conservative souls who no doubt found the nudity too much for contemplation in their living room. Norton did murals for many P&E commissions, and once upon a time dropped the ball. In a Parabiographies entry, Purcell recounts how work slipped through the cracks much to the dismay of the client and the architects. When the murals done by Norton for the Alexander Brothers Executive Offices library were ripped from their moorings, Purcell was contacted to see if he wanted to buy them. He declined, somewhat exasperated by what he considered a ridiculous price. Somewhere they are still out there.

Finally, one of the great treasures that appeared for the Minnesota 1900 exhibition were the two cartoon sketches for the murals in the Merchants Bank in Winona. Alas, I did not get photographs of them. Perhaps I can manage that yet.

COMING ATTRACTION: Housekeeping, including reviewing commission exhibits where enlarged images have not been linked! I see that the Parabiographies for 1914 need to be completed, as well. And there are more working drawings to be scanned --which are the least referenced of all the images available on the site, but which are still important to understanding the process.

10/1/2003 (addenda, 10/3/2003)

Cover for The Minnesotan (April, 1916)

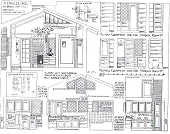

P&E entry, Minnesota State Art Commission

Brick and Tile Competition, 1914

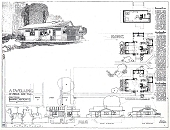

P&E entry, Brick House Competition (Sheet 1) Minnesota State Art Commission, 1917

P&E entry, Brick House Competition (Sheet 2) Minnesota State Art Commission, 1917Double Whammy, Redux. As early prophesied, a word often favored by Purcell in his latter decades, herewith scans of "Made in Minnesota," an article by Purcell which appeared in The Minnesotan (April, 1916 [vol. I, #9], pp. 7-13). The text expands into stone and brick the message about wood presented in an address to the AIA, which later become a pamphlet called "Forward Looking Salesmanship in Forest Products" (earlier added here, with commentary). Some of the same photographs of logging and mill-finished product also appear.

The Minnesotan was the official publication of the Minnesota State Art Commission, a unique officially state-sponsored organization intended to prosper the cultural development of Minnesota in a quite wonderful democratic way. In addition to publishing the magazine (see scans of two sample texts just added) there were also annual exhibitions at the Minnesota State Fair, and these often included architectural competitions to design affordable small homes. Such plans were then provided for a small charge to the general public, who might not otherwise have access or be inclined to seek out professionally conceived dwelling designs. Thus was Minnesota to become a better place to live.

P&E entered several of these competitions and individual Team members, such as Lawrence A. Fournier, did as well. The program was usually themed toward a small home whose construction emphasized a particular building material, such as wood, brick, or tile, and a limited level of expense whose hallmark was middle class affordability in the days before the home mortgage. The April, 1916 issue with Purcell's article contains the plan for a $3000 "Village House," whose boxy floor plan by Jerome Paul Jackson is--alas--not akin to the open flowing domestic tendencies of P&E. However, the architectural program is significant more because it would eventually evolve almost directly into a national program sponsored by the AIA and endorsed by the US Department of Commerce called the Architect's Small House Service Bureau (ASHSB) during the 1920s.

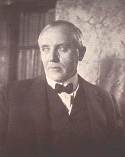

Portrait by Purcell

(1923)

Logo for the ASHSB, designed by John Jager

<-- "The Cave," home of the P&E archives for 35 years in the river rock-walled basement of Jager's house on Red Cedar Lane, south Minneapolis Purcell participated in the ASHSB from his Portland office. Several small houses designed by him were published and sold as prepared sets of plans. While it is little known, the official "logo" for the ASHSB was drawn by John Jager in what was--for him--an unusually public expression of participation. Jager was more inclined to hide his work, something illustrated by two circumstances. At his cabin at Lake Vermillion in the north woods of Minnesota, Jager spent an entire summer constructing a finely wrought flagstone walkway that started nowhere and ended nowhere. He then buried the whole thing, sending a letter (and photograph) to Purcell explaining that such an archaeological mystery was his legacy to the future. As if anyone might ever dig it up... As it happens, the metaphor would prove lasting.

Jager died in 1959, but his widow Selma lived on until the early 1970s. The P&E records remained in the basement of the "Cave" at Red Cedar Lane in south Minneapolis until being transferred to the University of Minnesota around that time. While she could not dispose of the P&E materials, Selma did order her executrix friends to burn all remaining documents of her husband's. These included not only decades of original research by Jager in the Etruscan culture as well as voluminous other manuscripts and correspondence, but also countless photographs he had taken of China when assigned there to rebuild the Austro-Hungarian legation following the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. Only some few architectural drawings--stuck by Jager into the very walls of his house at some earlier time--survived to be discovered by later owners during a wholesale remodeling of the former "Cave." These included a couple of renderings from his years at the Vienna Polytechnicum, as well as some churches he had designed for sites in Minnesota.

Advertisement for John S. Bradstreet Advertisement for Harry Franklin Baker, landscape architect The Minnesotan issue also has a couple of advertisements of interest. The Crafthouse of John S. Bradstreet in Minneapolis produced special high quality interior designs with an exotic, frequently Asian flair. Emil Frank, Jr., a P&E drafter during 1914-1915 or so, was the son of a Crafthouse cabinet maker--who also executed the Mrs. William H. Hanna dining room suite (Chicago, Illinois 1915). Landscape architect Harry Franklin Baker chose the soon-to-be unfortunate "The City Beautiful--The Home Beautiful" phrase for his ad, as the City Beautiful movement of the 1920s was in part responsible for the loss of an audience for the Progressive architects.