|

firm active: 1907-1921 minneapolis, minnesota :: chicago, illinois |

Ye Olde Grindstone

10/20/2006

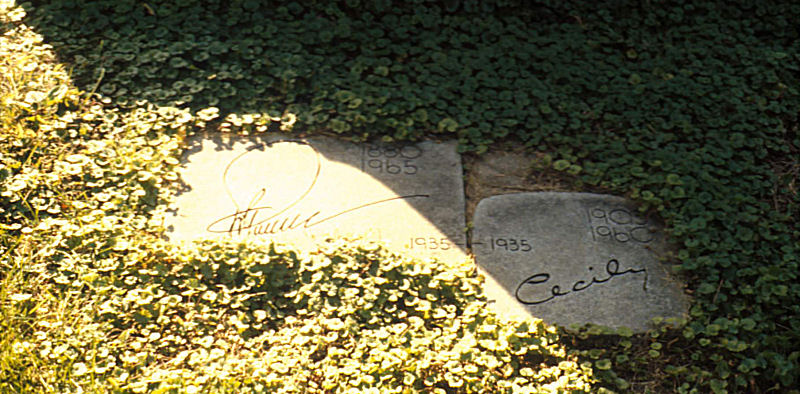

Grave marker plates for William Gray Purcell and Cecily O'Brien Purcell

Designed by Purcell, made by Alphonso Ianelli, and installed in the dead of night by Richard Nickel after the cemetery said "no."Portcullis. The Purcell and Elmslie pages of Organica are the number one return on Google for the subject. That is something of an accomplishment for a non-commercial site. Frequently the top results for a search yield the "sponsored" (read: paid) returns, which are often related to major players like eBay and other merchant venues; such automated results are sometimes patently nonsensical, too. The contents of this P&E site are also listed first on DMOZ, the Open Directory Project, the "largest human-edited directory on the web," with the caption "Extensive overview of firm's work, largely drawn from the Northwest Architectural Archives at the University of Minnesota." That, of course, refers to the fact that about half of the content of this site reflects or is sourced from the William Gray Purcell Papers, and much of that through the "William Gray Purcell Job Files" segment of the Images digital database, both of which are housed at the University of Minnesota Libraries.

Beyond the documents from the Purcell Papers, there are appear here research materials from over thirty periodicals or other publications contemporary with P&E; extensive documentation of standing buildings by several architectural photographers, particularly those images

Credit: Photograph by Scot Zimmerman

supplied through work done out of a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts; images from HABS at the Library of Congress and other digital collections provided by public repositories; numerous records supplied by descendants of P&E clients, current owners of their buildings and objects, and interested passersby; plus whatever value my own writings and links to external resources have added to the whole. A quick inventory shows a substantial standing backlog of contributions that I have not yet been able to get coded into HTML or logged into HyperFind.

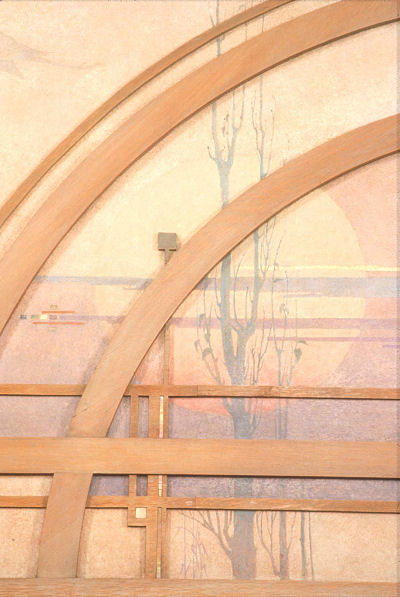

Mural detail

Charles Livingston Bull, artist

Edna S. Purcell residence [aka Lake Place]

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1913

Even so, the contents of this site have reached something of a milestone. Periodically the web logs that record visitor usage of the content get analyzed, and some interesting numbers have arisen. Including the HyperFind-based returns, which are database generated and provide indexed access to the 700 written page Guide to the William Gray Purcell Papers which I authored in the 1980s, the P&E site now consists of over 4,000 individual web pages. These pages display approximately 5,000 images (including PDFs) of one form or another, though a portion of that count reflects various versions or enlarged details of the same root image. The pages of the related (old) Progressives On-Line (also an original HyperFind demonstration project) and The Prairie School Exchange segments add even more, but these notes are concerned more directly with the P&E part of the Organica domain. As noted on the "Site History and Specifications" page, this site has been in existence in one form or another since March 29, 1995, with a brief interruption of service when I was at Taliesin. In other words, P&E were among the first to have their message taken to the World Wide Web and thus, the Internet. I did not accomplish this alone, either. The original permission to publish documents from the Purcell Papers was generously given to me by Alan Lathrop, Curator of the Northwest Architectural Archives, in 1994 as part of the HyperFind demonstration project. Despite some recent downtime because of equipment failure, HyperFind still serves much of this site in the way intended and is being further developed. Swaths of what appear to be regular HTML pages are, in fact, generated on-the-fly by this data management system that was built through the commitment of David J. Klaassen, Professor and Curator of the Social Welfare History Archives, and other supporters at the University of Minnesota Libraries who allowed me the opportunity to create and pursue at will a cutting edge research and development project (a scary venture to a university library, which covets the comfort of existing standards). The product was praised in my presence by the director of the National Digital Initiative project at the Smithsonian and presented at several major conferences, including a national convention of the Society of American Archivists.

The fact that anyone at all uses these P&E pages today is a direct result of that historical continuum. The web log analysis shows that just over 18,000 unique individual users, excluding web bots like Google, Yahoo, MSN, and so forth, have accessed the Purcell and Elmslie entry page since the first of 2006. Not everyone stuck around; some people looked at just one page, while others looked at hundreds. Some people logged less than three seconds on the site, obviously glancing at a page for relevance to their original search query, and there were those who logged more than fifty hours of usage. Although the number is blurred by combining various web log formats over the years and some log files are missing outright, there have been about 80,000 unique visitors from 68 countries (again, exclusive of web bots) since the site came back up in 2001. With all the details shuffled behind the curtain of those most general numbers, that is the size of community here. P&E are doing pretty well for a long shuttered architectural firm fast approaching their centennial.

This Grind has a regular monthly readership averaging 275 individuals. I have to admit I am a bit stunned at that, especially since the sole link to this column was for years only a small one in tiny font at the very bottom of a long home page. Perhaps two dozen have communicated with me over the past five years. Half those have contributed information or photographs to the site and most of them have become regular correspondents who share interest and passion of various degrees and kinds. Some I hear from weekly, some perhaps every few months. That is my continuum in the Caravan, en route, and we are all under attack. When the House of Representatives changes hands in the next election, there will be a lame duck session of Congress that may result in the destruction of the principle foundations of the Internet that made this site and many others possible, all for the engorgement of telephone and cable companies.

I will not take space here to iterate the basics of the situation, as you can readily get to understand the term and history of net neutrality on a Wikipedia page. This issue is so important that even MoveOn.org and the Christian Coalition are working together to maintain public trust and equitable access to the Internet as they have existed for the past decade. Clearly this is a cultural and social values issue, not a political cause, as the combination of those strange bedfellows demonstrates, even though the action takes place in the realm of politics. I urge you to look at the issue on behalf of the democratic principles on which this site, and the content of this site, were built. What is happening here in America is being mirrored in the European Union, which just passed a new law that will lead to the requirement of having a government license in order to operate a web site. You can just see the American corporate suits saying, "Doh! Why didn't we think of that?! More revenue to renew the license yearly, just like we invented a fortune from thin air by making domain names due and payable annually!" I spend a thousand dollars a year already, never mind equipment costs and my labor, just for the technical services that keep Organica visible. Who gets that money, do you suppose? The same people who now want more by voiding the principle of net neutrality.

Andiron

Henry B. Babson residence, alterations

Louis Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie, architects

Riverside, Illinois [demolished] 1907/1908

Alterations by Purcell & Elmslie 1914

Collection: Chicago Art InstituteThe creation of the Internet was the greatest blow for personal freedom since the invention of the printing press. In one fell swoop the corporate lock on information dissemination emerging from concentration of media ownership was dialed back to fair play. Anyone with a computer and a connection could get their voice out there at very little cost. Please take the time to to read about net neutrality. It is my hope that at least 275 people will look into it, as that seems the full extent of my sphere of influence here. What anyone does or does not do is, of course, their own ball of rubber bands.

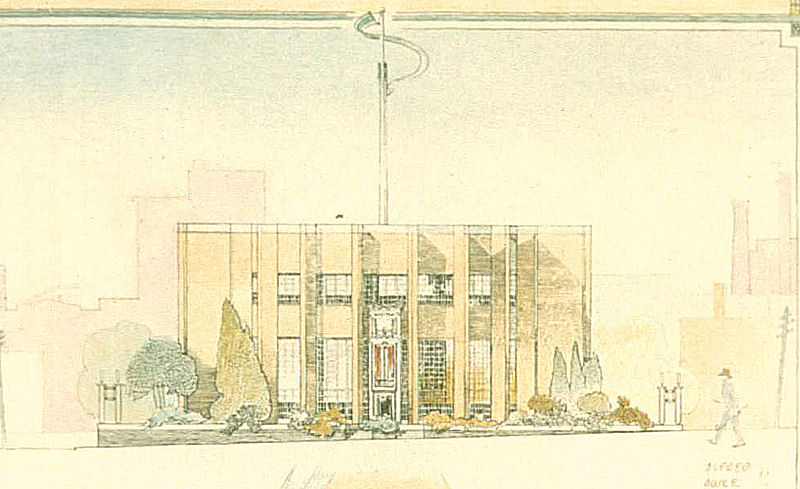

Detail, presentation rendering (enlarged from a 35mm slide made by Purcell)

Gusto Cigarette Company, project

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1914Other News Department. On a more cheerful note, a Grind reader with whom I have exchanged notes on various texts requested that I write comments on books and other resources for the study of Progressive architecture. The thought had earlier occurred to me, too, but was shelved for lack of time. However, the two new books on P&E, together with an existing bibliography of the many texts within which their work is discussed or displayed, brings me to reconsider the investment of energy. I have also found numerous related texts on Google Books that can also be referenced fairly quickly. I'll take a shot at it over the next few weeks to see if there is any use by those who come to the site.

Also, several readers have suggested that I put a donation button on Organica for those who want to offer their support. I said that I have been reluctant to do this, because this site is a work of my heart and an offering to Spirit. "So is my click on the donation button," replied one quick mind, who had downloaded my somewhat massive Progressive bibliography from The Prairie School Exchange and said I saved her "countless hours of effort." Thus chided, I have put a donation button on the Organica home page. However, I want to make it very clear that this is not a solicitation of any kind. My work here has been and ever shall be in the nature of paying forward a gift. I can only thank those who want to sing along.

This Grind was up a little early, as I am about to enter into a production cycle for some contract work. The next Grind may be also a little delayed, depending on how fast I can crank on creating these other web sites and database. Bear with me.

10/15/2006 Desktop Image

by Tom Shearer

National Farmers Bank Right click and "Save as:" or

link opens new window for full view Precision.

Still into the guts of Visual Studio Web Developer 2005, so again musings

about my P&E book. These comments are the last in this line, as they deliver

me to a threshold. Offered above, a new desktop image in two exciting

resolutions contributed by Tom Shearer. I vote yea! In Pat Gebhard's kind acknowledgements of

Organica as a resource in the recently published Purcell & Elmslie:

Prairie Progressive Architects, which is a redaction of David Gebhard's

1953 doctoral thesis, she says: "Hopefully this book will be an

introduction to the firm's work, leaving room for Hammons' more exhaustive

treatment later." Pat Gebhard called me before she started

her endeavor and asked me about my approach. I gave her the nickel tour,

indicating that my interests and focus were more intent on the philosophical

and historical rather than the architectural, per se. I said that I intended

to continue the direction indicated in the first pages of the

Minnesota

1900 monograph published in 1994. I spoke of Sullivan and Bragdon,

Einstein and Minkowski, and shudder of shudders, the fourth dimension. As I

mentioned last week, these indicators are bulwarks in understanding the

spiritual nature of design found in work by Purcell and Elmslie and thus

discerning their true motivations -- anathema to many minds, then and now.

Having been in this line of fire for more than twenty-five years, I am well

aware that for many people who might approach an "exhaustive" treatment of

P&E looking for every doorknob, such metaphysical discussion could prove less than satisfying. During the last few months my thoughts have

been occupied with discerning and articulating the true purpose in pouring

my energies into a book that has wanted to be written for an extended

period. Often my inner critic has both

shamed and lamented the quarter century involved with thoughts that there

was something faulty in me for requiring a lifetime of experience to rise to

the maturity of being able to write their story with fidelity. There has

also been the absence of my training as an architect. How can I presume to

discuss the work of architects, especially intensely gifted ones, without

having their same frame of professional reference? And, lastly, the real

kicker, trust: who is to say that what resonates in me from beginning to end

in everything I have ever encountered from their hands, whether built or

written or drawn, is actually the same thing they intended to convey? Assuming for a moment that I can reconcile

all those issues, and work remains to be done which we get to below, there is another major

consideration: Do I produce an "exhaustive" study that sets out their

production with the finality of a tombstone, inarguably precise accounts of

when "who did want to whom" resting upon inviolable caissons of footnotes?

Or, do I

go for something "exhaustive" which, forgive me, has an actual comprehensive

relevance to our present day lives? Do I report their message as a static

dispatch from a battle fought long ago, or do I seek out the still vital

dynamic tendrils of their cause

so as to shift consciousness forward rather than backward? If I go the latter route, which has always

been there like whatever is in Loch Ness, that raises the question of the

vehicle. If I produce a scholarly text, what audience is there for the 1500

copies, perhaps, of a hard cover printed once? And, importantly, is that

audience the same one that P&E would mean to reach? Do I want to have

spent all this time getting to the sticking place only to address a

sprinkling of academics, architects, and already interested lay people? Or,

how about a modified Devil and The White City approach? Shall I

report the War as a mystery yet to be solved, la The Black Dahlia?

(I mention that only because I was last night in the building, for a dance

performance, where her dismembered body was discovered -- write from your

own experience, they say. Everyone was asking me if I could sense the

ghosts. There are apparently more than one. Sorry, no juice.) Thankfully,

the coffee table approach has already been taken. Having sat my share place

holding in various living rooms, I know how those books get used to kill

small interruptible segments of time. Pictures are pleasing, of course, but the

appearance of beauty alone does not explain the nature of the intention nor

the substance of the effect. To perform properly in conveying the mind

beyond the surface, words must be more than a mere technical reflection. Not

only must the depth of beauty be rightly encompassed, but also integrated

with understanding that plumbs past the visible. The only way to do that is

by establishing a viable metaphysical framework within which the discussion

of P&E can be unfolded. The conundrum is doing so without triggering

modernist rejection. The truth is that many people I have encountered in

tendering these considerations lapse to a default position derived from the

hard core conditioning of material reductionism which says, "There is no

such thing." Some correspondents who respond to these

Grinds complain when I "wander off" into the kind of discussion that turns

on this issue of spiritual intention. "Let things speak for themselves," was

one admonition. To me, that is just the problem. The artifacts illustrated

in books or electronically are not the actual perception of the thing in

person, nor when arrayed like the Black Dahlia in galleries can many P&E

objects be experienced as living things anymore. In the past through

extraordinary circumstances I was extremely privileged to live with

P&E furniture and artwork for years. When I look at chairs I once sat upon

daily now shelved on the pedestals of museums, I hear a distant, ghostly

lamentation for use. (The only answer to preservation seems to be

reproduction, and in copies there is always the whiff of the fakery against

which P&E were so adamantly opposed.) The book, through words, has to

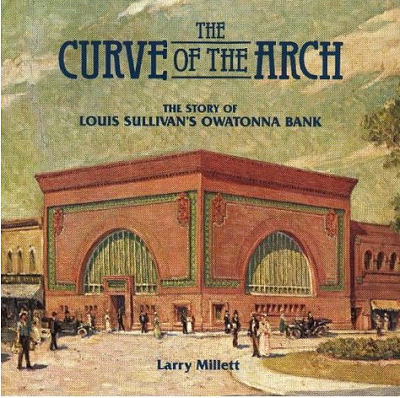

provide that missing element. Larry Millett, a newspaperman whose The Curve of

the Arch remains the best exposition of George Grant Elmslie yet

produced, once critiqued my very earliest 1980s essays on Purcell as

verging toward "hagiography." No nonsense, those newspaper fellows. He

was probably right, though that wasn't my intention. What he detected

was the upwelling of my fledgling recognition of virtue in the cause P&E

pursued -- and you know how the hammer of epiphany can make everything

a nail. These same essays form the core biographical content so far on

this site, so you can judge for yourself whether I was proselytizing for

saints or just heroes. Education was a primary function in the

work of Purcell and Elmslie, a task Purcell carried on for the rest of his

life in the many publications and correspondence he produced. If I just

report all that as curriculum, like a ledger with a nice gloss, easy enough.

But I believe I would fail in revealing the real essence. In that failure

would arise another: meaningful relationship to our own present moment of

experience. How do I chop the wood and carry the water in such a way as to

avoid hagiography and the dusty well of historical reminiscence? For a few

nanoseconds I considered novelizing the continuum, but instantly the ability

to point directly to the underlying source would be lost. To think I once

despised footnotes and now cajole them to remain present. I have ever

been a novelist at heart and, heading that way even now, this production for

P&E may well be my final scholarly efflorescence. Since neither love poem or dry gulch is

appropriate enough to be effective, I am left with the organic solution.

Whatever form I come up with is going to be designed and executed in the

here and now, fresh and relevant to our own time and place. P&E are not

fodder, either, for my own inclinations. As I noted above, there is the

question of projection. After this long on the trail, however, I have come

to accept my insights with enough respect to find sincerity in their

expressions. That's the best I can do. George Elmslie might have turned it

out thus, with a line drawing shaken out of his sleeve which I must, alas,

borrow: As for the "writing about architects

without being one" question, I think I have come to an acceptable answer.

Many architectural historians are not architects. I've been around a wide

variety of architects, organic and otherwise. I have worked with them, in

and outside of their offices, for a

long time and learned who they are as a class. Even considering variance

from personal idiosyncrasies, their attitudes and behaviors are pretty

consistent. I go with a sense combined from historical documents and

personal acquaintance that they have mostly always been of a kind. A number of

architects have been interested in pointing out to me (their view of) what

P&E were accomplishing from a technical perspective, so I get that end of

things several times over. Perhaps my view from the outside looking in

possesses a desirable neutrality. In reverse order, as it turned out, there

is my question about the length of time it took. In truth, I now possess the

confidence to tackle the whole shebang in the terms outlined above. There

was no real error or failure to perform heretofore, despite the mileage of

the journey. Life was what it was, abiding. This book is not about me. True,

the knife got sharpened. I am a vastly better writer, my experiences have

taken me into many relevant lessons, and I have clarity and capacity for

discernment that was formerly obscured though not really absent. My efforts

are not rooted in the necessities of an academic career. The real issue

turns out to be this moment in our cultural lives, where a renewed call to

spirituality as a practical moral function may serve to do as P&E meant to

do, demonstrate the way to a better future, only now as examples from the

past that show it can be done. As it turns out, serendipitous decades and

all, I came to be one Johnny on the spot. No, I didn't have the awareness to

plan things out. Mark 0, Pookies, 1. Last Grind I noted that the scarcity of

persons in my acquaintance who had read the Minnesota 1900 monograph.

True

to synchronous form in the way of my experience in the Caravan, the very

next day I happened upon a citation of my effort with the adjective "superb"

applied in a footnote of "The Prairie Spirit in Landscape Gardening," a

reprint of Wilhelm Miller's classic introduced by Christopher Vernon. I

remember taking Chris around Minneapolis when he came to visit the Purcell

Papers in the early 1980s, before he emigrated to Australia. Every time we

have corresponded something has happened to interrupt the flow, such as my

last contact with him just days before fleeing -- er, leaving Taliesin West

five years ago. I remember he asked me about Wilhelm Miller, too, and P&E,

to which I failed regrettably to respond. I see he was able to find

out. So, the Caravan works in mysterious ways. Lastly, there is the matter of finances.

Somewhere, somehow, the resources to support production of this book are

going to have to be manifest. Life has been clear that I cannot

simultaneously struggle for a living and write at the level required for the

P&E endeavor. Sorry, I just ain't Superman. Gone, too, are the days of

grants come (often) unsolicited from Purcell's friends, who have mostly

passed on. And the income obligations of grants since Reagan's tax law change

of 1987 mean you have to get a third more than you actually need in order to

have enough. A careful estimation of the research and travel costs, and

support of the writing time, are bottom lined at $30,000 on the church mouse

standard. The theory of having a year or so to work uninterrupted on this

one project seems fantastical, but a book I

have been reading, Ask And It Is Given, insists that all things are possible with the right heart.

The question is, of course, who to ask. As my dear friend Mardik Martin, who wrote Raging Bull among other

Scorcese films, says, "We shall see what we shall see." And so we shall. Since these are concerns now aired and settled

sufficient to the need, the Grind hereafter shall be in a more traditional

vein. That'll make some readers happier, I know. Eye to Eye.

Still working backstage in developer software, so this Grind is more of a

musing than reportage of new goodies.

Recent conversations with good companions who

have never heard of Progressive architecture brought home to me afresh how

very narrow is the lancet of light that constitutes this particular stream

of consciousness. Bright, well-educated, intelligent and sensitive people

lead a fully productive modern existence without the slightest shred of

awareness about Louis Sullivan, George Grant Elmslie, and William Gray

Purcell, never mind the rest of the goodly company.

Of course, they recognize the name of Frank

Lloyd Wright, equating him mostly with the work from the last few decades of

his life. Without apology, they think of him as retro, simply a market niche

of reproductions like Tiffany dragonfly desk lamps or leather covered

Corbusier chaise lounges. These friends of mine are not shallow people nor

are they lacking in interest. They lead engaged lives in the big city. Fully

conversant with the contents of the Museum of Contemporary Art, for example,

and possessing season tickets to the numerous cultural venues, busy as they

are with the living arts they just have had no occasion to encounter

something as "remotely historical" (read: Midwestern) as Purcell & Elmslie.

Aye, there's the rub. As of February, 2007, precisely one hundred

years will have elapsed since the firm to become most widely known as P&E

opened their first city desk. By the very nature of things their physical

presence has been eroding ever since the last one closed in 1921. I remember

this sense of elapsed distance being brought home sharply in July, 1980,

when I was talking on the phone with Dorothy O'Brien, Purcell's

sister-in-law. Dorothy lived out her final years in a retirement community not far

from the "Westwinds" estate in Monrovia, California, where she had come

after serving with British Intelligence during World War II to

live with sister Cecily and her husband. I had called her, among other things, to say she would have an

honorary presence at Purcell's 100th birthday dinner party being held at my

house that evening. "That can't be!" she exclaimed. "Surely

Bill isn't a hundred years old! What does that make me?" In 1994, I wrote what was called

the first published monograph on the work of the

firm for the Minnesota 1900 exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art,

published by the University of Delaware Press. Aside from the fact that

there was the required review of the P&E canon and an iteration of the basic

biographical facts, the explication of organic understanding I cobbled up in

the front eight pages was the first text since the 1920s to discuss their

work as the consequence of spiritual awareness and intention. I remain proud

of those introductory paragraphs, and I have yet to say it better. Sometimes

I do wonder whether or not there is really any point to writing "my

book" on P&E, though I am always encouraged past those doubts by some

higher dedication. To this day, twelve years later, I haven't

met altogether ten people who profess to have read the 1994 effort. Perhaps two have ever

discussed it with me, one being the editor. My fine aforementioned friends

expressed astonishment that I had published such a text, not because they

doubted my capacity but because they had known me for five years and not

read a single one of my books. This has happened before, repeatedly.

Usually, I responded by lending a copy. Right now, I don't even possess the

published version of this monograph because I can't remember the last

borrower who, breathlessly, just had to have the book. That was in June,

2005, I think. Odd that I can recall when, but not who. While I observed my

loans being given a place of honor for months on various coffee tables, the

return to my hands was always accompanied with a sheepish apology for

keeping it too long and, oh yes, sorry, "I just didn't have the time to get

around to reading it." The punch line is inevitable: "I did like the

pictures." Even in this appalling result, there

is a lesson to be learned. People today, to use a modern colloquialism,

just do not get what Purcell and Elmslie were all about, even when

they are physically surrounded en toto by the crme de la surviving

crme. Never mind the further diminution of understanding possible from body

parts offered up as individual objects de virtue on the stands and

walls of museum galleries. The source of this disconnection is not due to a

failing of P&E, but rather the fact that the daily lives of most people have

been thrust away from the moral and ethical premises of Progressive design.

That photographer in the Lake Place living room was not there inspired by the love of spirituality, but to

earn a living in the here and now. Having been involved in Hollywood as

production designer for feature films and having otherwise accompanied

various architectural photographers to numerous sites, I can tell you from

firsthand experience that these media-based people are concentrated on

their art, not the refinements of artistic understandings on the part of

the subject. They will dress the moment with their own conception of

what can evoke interest or, at least, curiosity -- which is to say, imply

activity. In many architectural photographs the

purpose in this is easily detected. Wadded up newspaper combusts quickly to

give the illusion of wood burning in the fireplace more cleanly, neatly, and

more importantly quickly, than real logs might. The same vases of flowers

and candles serendipitously appear in different rooms. Wine glasses, bottle,

and corkscrew show up next to the bathtub and then, later, on the kitchen

countertop, still unconsumed. The new thing is to frame the room in perfect

focus with a human being, who is blurred to indistinctness by motion. Scale

without identity, I guess, which somehow seems perverse given that

architecture functions to transmit, well, identity. Whether the result is

intended or not, the outcome well illustrates that people pass anonymously,

perhaps even meaninglessly, in relationship to these mostly corporate

interiors. Like Sullivan, Purcell and Elmslie spent

themselves wholly in the struggle to establish an American architecture

based on an honest expression of the unprecedented conditions and qualities

of our democratic life. The life they designed, and hoped for us to lead,

did not survive the consequences of world wars that were, actually, one

conflict with a generational intermission to restock the soldiery. The

massive industrialization of architecture that occurred afterwards to give

every GI Joe a home replete with standard amenities and two cars, as well as

house the burgeoning pathology of corporate systems developed to deliver the

goods, completed the entelechy of machines within which our spirits are now

mummy wrapped. All this, of course, is a natural outcome

in the triumph of material reductionism as the one, the only valid and

allowable mindset. Western culture has enveloped, or more accurately

purchased, the entire globe with the premise that there is no such thing as

spirit. The average secular American is completely trained to reject as

unreal anything that cannot be quantified -- and bought. Fie on the fourth

dimension! The copious writings, techniques, and remains of the people who

came before our armies of white coats in laboratories are therefore merely

expressions of delusion, quaint but untrustworthy. As we move forward amidst

the ever intensifying pressure of mere station keeping in this world, our

attention span becomes increasingly tightened down to smaller and small

increments of time. Commercials that once took a whole thirty seconds now

stream by as three or four in that same period, for example. What means a

century in that context? William Gray Purcell, the eternal optimist, would

tell you: "Hope and faith in the basic goodness of people." What remains of

what was may yet find a means to take us to what will be. Write the book,

Mark! Yes, I have rattled on, but these words

give an inkling of the issues, themes, and continuities flowing through my

mind as I contemplate the work schedule for completing my final offering to

the Caravan on the subject of P&E. I am going to have to find a way to

overcome the detritus of material reductionism and the effects of spiritual

denial on the modern mind. Hmmm. Most people didn't listen the first time

around, as P&E knew. Maybe I just need to get some flowers and a bottle of

wine. And I end this peregrination with the pleasure of a comment from a

constant reader, who says that I "write like Purcell, full of sentences that

are too long because you try to say too much." I prefer to take that as a

compliment, noting there is a lot to be said, though I also take notice of

the advice to speak plainly in smaller bites. However much I may abjure the

loquacious realm later, the Grind is still my sandbox. Have a great week.

Louis H. Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie, architects

Owatonna, Minnesota 1905

Postcard

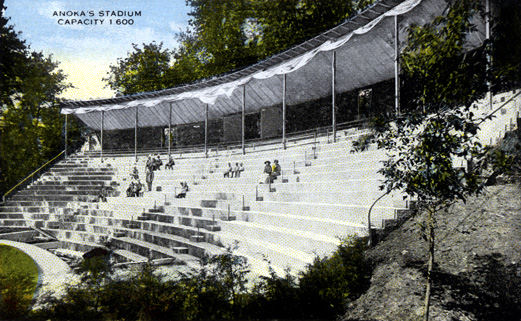

Open Air Theater for Thaddeus P. Giddings

Anoka, Minnesota

1914/1915

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries online U Media Archive, University of Minnesota Libraries

Detail, perspective view

Service Buildings for Henry B. Babson

Riverside, Illinois 1915

Source: HABS

What I propose to write

must answer the call to living function, not be a virtual museum of

facts and analysis that lets anyone stray anywhere their personal

palette prefers. What it boils down to is that P&E created a whole

environment. That was their design goal, and such was possible because

they related to the context of the surrounding world as holism. The P&E

book must be a form of discovery that bears the reader beyond fragmented

mental pigeonholes.

Cover

Published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1985

A

minstrel shall I be,

for the twenty-first century.

Fireplace detail, banding finial

Edna S. Purcell residence [aka Lake Place]

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1913

Detail, postcard (b&w here,

sepia on brown paper in the original)

National Farmers Bank

Louis H. Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie, architects

Owatonna, Minnesota

Detail, postcard (b&w here, sepia

on brown paper in the original)

National Farmers Bank

Louis H. Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie, architects

Owatonna, MinnesotaWith mental recognition of the calendar dates

involved, Dorothy was genuinely taken aback at the evaporation of time. I

think it depressed her a little. There was suddenly visible an irrevocable

chasm of separation. All the good feelings and memories together shivered,

with the emphatic distance of the past somehow foreshadowing the eventual permanent

departure of the present. Something like that touch of mortality falls upon

me now, as I consider that reported event occurred over twenty-five years

ago. A quarter of a century fled by as I took my steps on, through, aside,

and occasionally away from the Path, pursued the tasks placed upon my

shoulders by the Cause, and joined in bouts of passage with those among the Caravan

whose footsteps appeared, here and there, next to my own.

One of the pictures published in that book

(I did not get to choose the

illustrations; and can't display here the one discussed because of copyright) shows the Lake Place living room, looking toward the great

east windows. Everything that belongs there is more or less present and

properly in place, minus of course and probably everlastingly the stenciled

curtains. However, something unnatural has been added. Right down the middle

of the carefully reproduced Elmslie-designed floor rugs the photographer has

gone upstairs to drag down a Persian runner which has been inserted

dagger-like into the heart of the room. Something spurious had to be brought

in for it to satisfy the contemporary eye, like the adventitious deposit

of an untrained dog. And is it just the fault of a photographer with

Victorian sensibilities? No. The image passed through many hands on the

way to publication, including those at the museum who should have known

better.

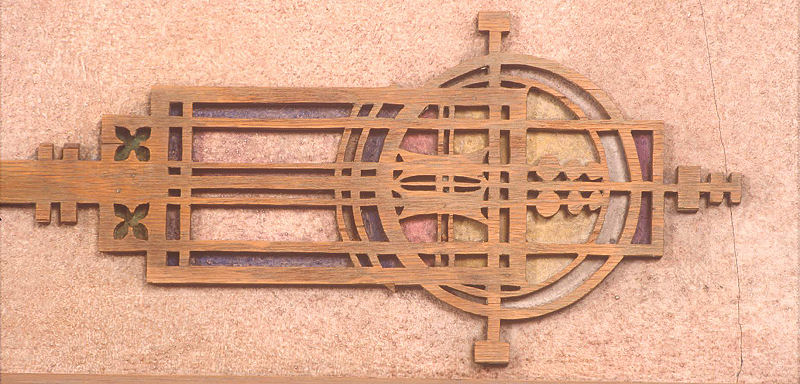

Sawed wood pattern for sideboard

Edward L. Powers residence

Purcell, Feick, and Elmslie

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1910

Terra-cotta module

Edward L. Powers residence

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1910

Source: University of Minnesota Libraries online U Media Archive, University of Minnesota Libraries

My view in writing about P&E![]() research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons