|

firm active: 1907-1921 minneapolis, minnesota :: chicago, illinois |

Biographical Notes: William Gray Purcell (1880-1965)

Biographical essay in Guide to the

William Gray Purcell Papers.

Copyright by Mark Hammons, 1985.

William Gray Purcell

circa 1920s

PORTLAND, 1920-1930

In 1919 Purcell chose a course of action that he hoped would renew the independence and freedom of thought he felt was lost during his time with the Alexander Brothers companies in Philadelphia. As in the years of his apprenticeship, his mind turned to the fresh, vigorous potential of the Pacific Northwest. The rich forests and rushing rivers were a potent reminder of his inspiring childhood experiences at Island Lake, Wisconsin, and the character of life in the region still relied on the free, pioneering spirit through which Purcell had first come to know his philosophical calling.

Leaving the East Coast in November, Purcell met

with a fortunate coincidence upon his arrival in Portland, Oregon. His old

school teacher, Helen E. Starrett, had left Oak Park years before and settled in

Portland. A nationally prominent feminist leader, Starrett was on her way to

Washington, D.C., to lobby for women's suffrage at a special Congressional

session called by President Woodrow Wilson. She gladly rented her house to

Purcell, asking only that he leave the car and the cook in the same condition in

which he had found them. Getting settled, he sent for his family, including

Catherine Gray and her companion Annie Ziegler who took rooms in the newly built

Mallory Hotel.

At first, Purcell did not intend to continue in architectural practice. His

original purpose in coming west was to join his cousin, Charles H. Purcell, in a

bridge building company called the Pacific States Engineering Corporation (PSEC).

A civil engineer who later designed the Oakland Bay Bridge, Charles H. Purcell

had lived in Oak Park during his adolescence with Charles A. Purcell, his uncle,

who subsequently financed his college education. With a loan from Charles

A. Purcell, an office was opened and an accounting system started for the new

partnership in 1919. Charles H. Purcell remained involved in government road

building projects that prevented him from fully participating in the venture.

Looking for professional work to occupy himself

in the meantime, William Gray Purcell found his interest naturally drawn back to

architectural design. The Purcell & Elmslie partnership still existed, and the

firm received credit for several works done during the first year that Purcell

lived in Portland. Two were unbuilt projects. George Elmslie drew preliminary

sketches for a resort hotel on the Hood River under a contact initially made by

Charles H. Purcell, but the scheme did not proceed beyond general discussions.

Elmslie also contributed to a speculative apartment building proposed for the

Portland area that was not constructed for lack of investment capital.

A bridge and a personal residence for Purcell attributed to Purcell & Elmslie

were built. Under the direction of Charles H. Purcell, the U. S. Bureau of

Public Roads had begun the design of a bridge to cross a small river called Wolf

Creek, and William Purcell commented to his partner that the concrete building

material was to be molded into historically derived masonry forms that he felt

would be neither efficient or artistic. Purcell was asked to assist in the

bridge design and wrote about the project to Elmslie, who replied that such a

structure was essentially architecture cast from point to point through the air.

These discussions led Purcell to contribute drawings for portions of the bridge

that created a more dynamic effect through use of the building material.

William Gray Purcell residence aka "Georgian Place" Purcell and Elmslie Portland, Oregon 1920 |

William Gray Purcell residence Living room fireplace |

The

William Gray Purcell residence

in Portland, known as "Georgian Place" after the street where it was built in 1920, was a

project in that the familiar productive interchange between Purcell and Elmslie

came into play for the last time. The building site was once the crest of a

steep hillside and had a beautiful westward view across six miles of forested

valley. An unusually precipitous grade on the site presented tremendous

construction difficulties. The design of the house evolved over several months,

with Elmslie sending studies from Chicago that Purcell revised from his

immediate knowledge of the location. Elmslie sought to integrate the hillside

atmosphere into the living arrangements. The window placement was a key part in

the composition because of the dramatic vista: entrances, hallways, and the

stairwell were aligned with casement openings to create the sense of dwelling

among the treetops. The effect was heightened through the addition of a balcony

on the north side of the house, and the positioning of the garage on the right

where a mature tree was left in place to create a miniature circular driveway.

In a stroke of humor, a bird house was attached to the chimney.

Beyond these few commissions little work was in prospect for Purcell during his

first years in Oregon, and he turned to a variety of architectural ventures that

attempted to market the services of architects to builders who would not

ordinarily consider them. Several related business schemes were intended to gain

architectural work for the Purcell & Elmslie partnership without using the

name of the firm, in order keep potential clients from thinking architect

designed work would be too costly. Advertisements for standardized plans for

banks and small houses were placed in various periodicals under company names

like the Cunningham Gray Architectural Service or the Builder's Plan Service. To

give the impression of established and flourishing businesses, these notices

usually listed the addresses for all three architectural offices one maintained

in Minneapolis by Frederick A. Strauel, in Chicago by Elmslie, and in Portland

by Purcell. One such advertisement that appeared in Banker's Monthly, a journal

to which Elmslie occasionally contributed articles on functional bank design,

resulted in a commission for the First National Bank of Adams, Minnesota. With a

design typical in character of earlier small town banks by Purcell & Elmslie,

the plans for the Adams bank carried the company title of the Builder's Document

Service.

Beyond one bank and a few other, fruitless inquiries, the effort to generate new

business was a failure. Citing poor economic circumstances, Purcell formally

requested that the firm be dissolved in 1921. Elmslie, who had no financial

reserves, was deeply offended and observed that his own contributions to the

office had often been worth more than the salary he had received. Besides, he

felt that the end of the partnership would be an admission of defeat in the

architectural struggle they had waged so earnestly. After some argumentative

exchange of correspondence about the distribution of minor office assets

when the Chicago office was closed, the two men eventually reasserted their

friendship.

|

Douglas Donaldson circa 1920s |

|

Announcement for art class

being taught by Douglas Donaldson circa 1920s |

As he did with his other new companies, Purcell created the appearance of

prosperity for the Pacific States Engineering Corporation (PSEC) by listing a

putative office in Los Angeles. During the early 1920s, he met Douglas

Donaldson, a color theorist and art instructor whose Graphical Designs were in

much the same organic spirit as the advertising work Purcell had done for

Alexander Brothers. The two men shared a common view of art as a process of

spiritual information, and Purcell arranged for his friend to give art classes

in Oregon. Donaldson reciprocated by serving as the interior design consultant

for the PSEC, and allowed his name and studio address in Hollywood, California,

to appear on the corporation stationery. Since the planned participation of Charles H. Purcell in the PSEC did not fully

materialize and only minor consultations came through the Donaldson connection,

the company became principally a developer of speculative residential

properties. Although a few unbuilt apartment projects were also designed, the

PSEC buildings consisted mostly of small houses located in scattered groups

throughout the southeast Portland area. These dwellings were meant for people of

limited means who wanted a higher quality residence than was normally available

to them. They had the same basic purpose as the many plans that were being

offered through various national magazine advertisements. The PSEC houses were a mainstay of Purcell's

architectural practice over the next ten years. Most sold for between seven and

nine thousand dollars, and many represented experimental solutions to the

special problems of the long rainy Pacific Northwest winters. For example,

window frames served as the structure of the dormers and so doubled the area

open to light, as in the In the first rental property built in 1922 for Eleanor

M. Carleton. Other houses of the same period tried new heating systems to

improve air circulation, while special shingling techniques and window casements

were developed to reduce penetration by the weather. Because the houses were

built along common lines within a limited budget using commercially available

materials, individual variations were introduced purposely to avoid similarity

of appearance. Special requirements of unusually shaped lots also contributed to

the functional evolution of their plans. Purcell also showed his interest in providing readymade designs and a democratic

accessibility to competent architectural services when he became involved with

the Architect's Small House Service Bureau (ASHSB). A national organization of

practicing architects endorsed by the American Institute of Architects, the

ASHSB encouraged the building of good quality small houses by offering

professionally designed stock plans. The ASHSB divided the United States into

regional divisions, with national headquarters in the same Minneapolis,

Minnesota, building where former Purcell & Elmslie chief drafter Frederick A.

Strauel continued to do extensive drafting for Purcell. For a time Purcell

served as an officer in the northwestern division of the ASHSB that included

Oregon, and at least one of his small house plans was marketed through the

organization. In numerous residential designs of the Portland period Purcell carried on a free

association with other architects. For example, Elmslie occasionally did

sketches for the PSEC houses, although they tended to be too complex and

uneconomical. Nearly all drafting for the Purcell projects in Portland was done

by Frederick Strauel, who came to Oregon to work for a time during 1922. Strauel

was also fully credited as associate architect with Purcell in a series of nine

houses designed from 1928 to 1929 for Minneapolis developer H. M. Peterson.

In 1925 Purcell met James Van Evera Bailey, a young architect who introduced

himself as the nephew of the plumber who had worked for Purcell & Elmslie

thirteen years earlier on the C. I. Buxton residence in Owatonna, Minnesota. A

warm relationship between the two men was quickly blossomed, and Bailey, who was

working for Portland architect Otis J. Fitch, eventually became an associate

architect with Purcell in many projects. In particular Bailey was an integral

participant in both the design and construction process for four houses built

during the Portland years. While Purcell developed the schemes, Bailey

supervised the construction details for the Harry S. Bastian residence at

Lake Oswego and the Sidney Bell residence next to the W. G. Purcell house in the

hills above Portland, both built in 1927. A year later, the John W. Todd and W.

H. Arnold residences in Vancouver, Washington, were Purcell designs fully handled by Bailey. In the Todd and Arnold dwellings, together with the

similarly conceived Wallace-Bradford residence, Purcell sought a more spiritual

as well as economic expression of his functional ideals by directly exposing

much of the structural building materials, and Bailey showed a sound grasp of

the objective by completing the work while Purcell was away on a tour of Europe.

The largest and final major commission that Purcell received was the Third

Church of Christ, Scientist, in Portland. Built in 1926, the building as

completed realized only part of his design. Based on ideas that had been first

considered in an earlier Christian Science project in Minneapolis, the planning

provided for construction in phases and began with an intended Sunday school

auditorium to which would have been added a larger main reading room as the

church membership required more space. Although in the Third Church of Christ,

Scientist, Purcell fulfilled a long held desire to design for this form of

assembly, he later admitted that subsequent alterations to add more serviceable

entrances were well justified and that some clumsiness in the first part of his

own program may have contributed to the failure of the rest to be built. While living in Portland, Purcell remained in

contact with friends and associates from his midwestern practice. His continuing

friendship with John Jager, who remained at work in the Hewitt & Brown office in

Minneapolis, resulted in voluminous brotherly exchanges of correspondence on a

vast array of scholarly subjects. Charles S. Chapman came to visit and enjoyed

camping trips with the Purcell sons. When Purcell heard the sculptor Richard Bock was

having difficulty getting work, he encouraged Bock to move to Oregon and was

instrumental in gaining him an appointment as head of the Department of

Sculpture at the University of Oregon. Bock welcomed the help and in

appreciation gave Purcell a duplicate model of the "Nils the Gooseboy" sculpture

that was originally placed in the Edna S. Purcell residence in Minneapolis and

subsequently destroyed in shipment to Oregon. Since architectural work continued to be intermittent, Purcell turned to writing

and began an articulation of his views on art and architecture that continued

prolifically until his death. Through his personal acquaintance with editor

Willis J. Abbott, Purcell sold to the Christian Science Monitor more than a

dozen articles on architectural design, particularly innovative construction

techniques being applied to bridge building, which were published between 1923

and 1927. He wrote a series of advisory columns called "The Lamps of Home

Building" and other contributions for The Small House, the ASHSB monthly

magazine edited by his friend Maurice I. Flagg, until that publication ceased

appearing in 1932. From 1929 to 1930, he edited the arts page of a Portland

weekly called The Spectator, in which he explored his interests in a wide range

of historical and contemporary subjects.

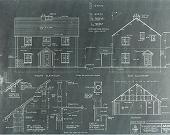

PSEC speculative house

Plan for the Architect's Small

House Service Bureau (ASHSB)

William Gray Purcell, architect

circa 1925

ASHSB trademark logo, designed by

John Jager

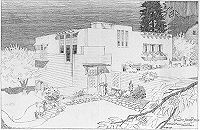

Sidney Bell residence: Presentation rendering

James Van Evera Bailey

Date unknown

Harry S. Bastian

residence

Portland, Oregon 1927

Purcell became increasingly active in professional, civic, and arts

organizations. In 1923 he was elected president of the Oregon chapter of the

American Institute of Architects, and from 1926 to 1927 he served in the same

capacity with the Oregon chapter of Pro Musica, International. To develop a

greater public understanding of the role of architects in the community, Purcell

initiated a group called the Architect's Research Board. He joined the Portland

Architectural Club, the Portland City Club, and was a moving force in the local

meetings of the literary Knights of the Round Table. From 1928 to 1930, Purcell

enjoyed painting on the nature outings of the mountain climbing Mazama Club, an

arts organization. One of the most significant and lasting results of Purcell's

involvement in the Portland arts community was the Oregon Society of Artists, of

which he was a co-founder in 1927.

During the Portland years, Purcell became repeatedly entangled in disastrous

financial arrangements. Real estate speculations like the purchase of the

Imperial Garage, a large car service and storage facility, were costly and

unprofitable. His involvement with the Guaranty Trust Company, which became

insolvent shortly after he invested, forced Purcell to turn for help to his

father, who had strongly advised against the venture in the first place.

Although the wealthy Charles A. Purcell continued to advance money, the repeated

errors in judgment shown by his son troubled their hitherto affectionate

relationship. These economic uncertainties were a severe strain on his home life

as well and aggravated an already shaky emotional relationship with his wife

Edna.

Throughout the decade, Purcell had felt a progressive decline in his physical

well being, feeling unaccountably tired and weak. Persisting in his Christian

Science beliefs, he ignored an increasing shortness of breath and continuous

fever. Matters worsened dramatically on a visit in 1929 to the forest cabin

owned by John Jager at Lake Vermilion in Minnesota, where Purcell suddenly found

himself unable to make even the most basic contributions to the camp work. In

spite of his condition, he continued to believe himself simply exhausted by the

stress and misfortune that seemed to have engulfed his life.

Eventually the situation grew sufficiently bad for Purcell to seek medical

attention. Reluctantly persuaded by friends to see a doctor in 1930, Purcell was

discovered to have advanced tuberculosis. Closing his practice and retiring with

a sense of failure from the new life he had worked to make for himself, Purcell

faced a dark and uncertain future.![]() research courtesy mark hammons

research courtesy mark hammons