|

firm active: 1907-1921 minneapolis, minnesota :: chicago, illinois |

Biographical Notes: William Cunningham Gray (1830-1901)

Biographical essay in Guide to the

William Gray Purcell Papers.

Copyright by Mark Hammons, 1985.

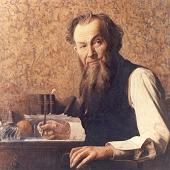

W. C. Gray

portrait by Lawton S. Parker, 1892

W. C. Gray

portrait by Lawton S. Parker, 1892

William Cunningham Gray was born at the family

farm in Butler County, Ohio, on October 17, 1830. Tall and broad shouldered his

commanding physical stature inherited from his forebears and strengthened in

manhood by the harsh demands of farm work was matched by a gentle and

intellectually inquisitive spirit. His childhood experiences in the largely

untamed wilderness surrounding the Gray homestead sparked a deep love and

respect for nature that remained with him throughout his life. In the beauty of

the natural world he found an inspiration that, from his earliest years,

directed the evolution of his thoughts.

At age ten, W. C. Gray discovered his vocation. When promised a supply of

pencils as a reward, he volunteered for the all night vigil of fueling the

boiling vats of maple syrup during sugar making season. Using a portion of his

payment that was supplied in advance, he kept himself awake by writing poetry on

the shards of discarded clay jugs. Those he liked best were cached secretly in a

hollow log until paper could be had to transcribe them. One poem submitted to a

local paper appeared in print, along with some words of praise from the editor.

Elated with this success, Gray resolved to make his living as a writer.

W. C. Gray soon demonstrated that his talents leaned more toward pursuits other

than farming. After rapidly mastering the grades of the local common school, he

convinced his father to send him to a private tutor at some distance from the

farm in order to learn Latin. The temperance movement was then strong in Ohio

and, at age fifteen, Gray took the pledge. His schoolmaster, a Scots minister,

was infuriated at Gray's becoming involved in such a serious political cause

while under his tutelage. At first threatening to whip the young man, he finally

sent him home with a note explaining what the boy had done. Jonathan Gray

surprised his fearful son by saying there would be no punishment unless the

pledge was broken, and the determined young man kept his solemn promise until

his death.

From 1848 to 1849, Gray attended Farmer's College

at College Hill, near Cincinnati. The members of his graduating class were a

remarkable group of young men, and almost all of them rose to pre-eminence as

congressmen, judges, lawyers, ministers, soldiers, or men of business. Here

began lifelong friendships with Murat Halstead (1829 1908), who became a

nationally known journalist, and Oliver W. Nixon (1825 1905), whose career as an

author and editor brought him fame. Teachers included the highly respected Dr.

Robert Bishop and Judge Josiah Scott, whose daughter married Gray's classmate

Benjamin Harrison (1833 1901), later President of the United States. Judge Scott

was impressed with the integrity and sense of fairness displayed by W. C. Gray

and encouraged his pupil to study law.

Gray passed his examinations in 1852 and was admitted to the bar. While in

college, he had supported himself with various jobs through which he learned the

printing trade. During the presidential campaign of 1852 he served as editor of

the Scott Battery, a Whig campaign paper published in Ohio. The year before he

had done work for a similar political organ, the Miami Democrat. These endeavors

only whetted his desire to write and, discontented with the work of a brief law

practice in Chillicothe, Ohio, Gray took down his shingle in the fall of 1853

and moved upstate to start a newspaper of his own in the river town of Tiffin

[3].

With money borrowed against his share of the Gray family farm, he opened a print

shop on the second floor of a building called Shawhan's Block. Every Friday for

the next three years he published the Tiffin City Tribune, whose banner line

proclaimed the paper to be "Hostile alike to the despot and demagogue...Fearless

for truth, for God, and humanity." Gray took seriously his role as the sole

local source of information, and worked long hours to make his paper both

interesting and useful to the frontier community [4].

The four pages of each issue contained a variety of announcements. Foreign and national news, reports of regional events, and official bulletins, such new city ordinances or foreclosure notices, appeared with the latest commodities quotations. Poetry and short fiction occasionally illustrated with cartoons provided entertainment. Letters to the editor were welcomed, and Gray sometimes set an example for those who needed one. For instance, one series of letters surreptitiously authored by Gray complained of attempts by a local merchant to corner the market in tea and opium. The proprietor of the Tribune lamented at the same time in an italicized note that these accusations were found on his desk unsigned. The back page of the Tribune was regularly given over to advertisements for pianos, coffins, patent medicines, and other mail order merchandise.

The paper was successful, but in each number the publisher reminded his readers of his extensive assortment of type styles for pamphlet and other printing work, as well as his willingness to do the work quickly and with the highest quality [5]. One such commission Gray received was to supply marriage certificates to a local judge. He took special care in executing these forms, composing them in an elegant new typeface and selecting the finest paper with his own special purpose in mind. His publishing business prospering, W. C. Gray felt the time was right to start a family.

William Cunningham Gray and Catherine Garns Gray, 1856

When he first proposed to Catherine Garns, a young woman with a reputation for both prettiness and popularity, Gray was at first rebuffed for impertinence. He persisted, undeterred by competition from a wealthy landowner and a state legislator, and the couple was married on December 2, 1856. While the future seemed to hold happy prospects for the newlyweds, their immediate livelihood soon became uncertain. Only a few months after their marriage, a local official whom Gray had bonded turned out to be corrupt and fled town, abandoning the debt. The Tribune and print shop were forfeited to satisfy the obligation. Left with very little money, the Grays moved to a small parcel of land attached to the family farm at Pleasant Run.

Life during the next five years was painful and

difficult. With hands used to the delicate if strenuous tasks of typesetting and

printing, W. C. Gray returned to the rougher labor of the fields. Catherine gave

birth to two children Frank Sherwood Gray (b. 1857) and Anna Catherine Gray

(1861 1914). Though glad of a home and food for his family, during these adverse

times W. C. Gray always hoped for an opportunity to return to newspaper work. In

1862 he obtained employment with the Cleveland Herald, but that job soon ended.

Rather than admit defeat and return to the family farm, he taught school at

Newville, Ohio. The time passed slowly for Gray, who suffered through long

separations from the wife and children he could not afford to bring along.

Good fortune finally came to the family in 1863. William managed to find a

position with The True American, a weekly newspaper published in Newark, Ohio. A

year later, when one of the principals in the business moved to Washington,

D.C., Gray learned of the opportunity to become a partner. His wife had

fortuitously come into a small inheritance and the money was invested in the

paper. The income was still insufficient to support a family in town, however,

and Catherine Gray and her children were forced to remain at the old homestead

until the end of the Civil War.

The editorials written by Gray for The True American were strong reactions against the atrocities of the war, the horror of which struck close to home. Catherine Gray received word in 1863 that a favorite cousin, Daniel Elliott, had been shot while held captive by Confederate troops. Only a short time afterwards, her husband joined in the fighting as a member of the Ohio Squirrel Gun Regiment raised to defend Cincinnati. Since the Grays were able to exchange only a few brief letters, these anxious weeks passed slowly; but eventually W. C. Gray returned unharmed to his newspaper.

In 1867 the family was once again brought together under one roof. Brother in law Andrew Ritchie became the secretary of the Western Tract and Book Society, a religious publishing house in Cincinnati. The position of treasurer in the organization was offered to W. C. Gray, who was familiar to the society through earlier contacts as well as having the recommendation of his relative. Selling his interest in the Newark paper, Gray took the post in summer of 1867 and established the Elm Street Publishing Company as a printing facility for the society. That same year his wife and children were able at last to quit the isolated farm and came to live in a small Greek Revival clapboard house not far from the print shop. The continuity of the family was at last restored, although Gray was frequently gone on business trips.

The Elm Street Publishing Company developed into a thriving enterprise. In 1867 Gray wrote and published through his presses a successful biography of Abraham Lincoln, whose death had greatly saddened him [6]. As a representative of the Western Tract and Book Society, Gray was required to travel to distribute the pamphlets and essays printed by his firm. For the next few years his activities took him across much of the Midwest, which he described in detail in letters to his wife back home. These railroad trips nonetheless sparked in Gray a fascination with exploring the American continent that in time would take him throughout the West and as far north as the Alaskan wilderness. At home in Cincinnati, William and Catherine Gray developed a circle of friends among the Protestant clergymen in the area who shared their open minded views toward life. One result of these acquaintances was the creation of a magazine called Our Monthly Quadrilateral. The title referred to the foursome of W. C. Gray, A. A. E. Taylor, Charles Lemuel Thompson, and O. A. Hill, who filled the pages with fiction and essays on Midwestern literature. Their collaboration lasted only for the twelve months of 1870, but the friendships from which the publication. was born continued through many following years.

|

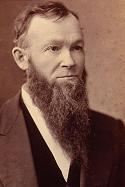

W. C. Gray, 1871 |

On October 10, 1871, an event took place in American history whose effects were of great consequence to W. C. Gray and his enterprises. The Great Fire of Chicago destroyed nearly eighteen thousand buildings, among them the offices and presses of various religious publications. As soon as Gray heard of the disaster, he sent word to the burned city of his willingness to print such papers and magazines on an interim basis in Cincinnati. Several. took advantage of the offer, including a Presbyterian weekly called The Interior.

The men who made the temporary printing arrangements for The Interior were much impressed by the learning, wit and geniality of W. C. Gray, and invited him to visit Chicago to see the firsthand the desolation caused by the fire. While there, Gray was introduced to various committees from the presbytery that owned the publication. A grim situation faced the newspaper. Morale was badly crippled by the fire and all that physically remained of the year old weekly was a scorched mailing list. Largely due to theological disputes between various editorial factions, The Interior had never enjoyed a strong circulation. Even supporters of the paper thought the destruction done by the fire presented an opportune moment to retire the enterprise. W. C. Gray believed otherwise and proposed to stay temporarily in Chicago to help get The Interior back into circulation. His reorganization plan was accepted and, after two months, Gray felt his work had been accomplished. When he returned south to Cincinnati and his own publishing concerns, representatives of the presbytery followed and persuaded him to make permanent his position as managing editor.

Gray sold the Elm Street Publishing Company and used the sixty thousand dollars he realized from the sale to buy new presses for the Chicago paper. Unfortunately, he also came quickly in confrontation with the divisive politics that had long plagued the editorial board of The Interior. A doctrinal conflict between two of his contributing clergymen swept away half the subscription list despite his best efforts to contain their bickering, and the paper was clearly foundering. Within two years his entire investment capital was gone. Faced with insolvency, Gray went to appeal for help from a man whose interest in the Protestant church was well known.

The benefactor he sought was not at the Rush Street mansion where W. C. Gray went to call, but the lady of the house received the editor instead. Nettie Fowler McCormick, wife of harvester magnate Cyrus Hall McCormick, was already familiar with the reputation of shown into her drawing room. She listened with interest as Gray described the situation faced by the paper and when the interview was concluded she sent him back to the Interior offices with assurances his worries were at an end. Shortly afterwards, in January, 1873, Cyrus Hall McCormick, Sr., purchased The Interior from the argument ridden presbytery and set the paper up as a private publication. The millionaire inventor had previously declined a direct interest in such properties, primarily to avoid the appearance of buying opinion, and the statement he published when the change in ownership was announced emphasized that editorial policy would remain entirely with the managing editor.

Relieved of financial anxieties and personality conflicts, W. C. Gray set out to make The Interior a widely read and influential journal. The newest, most advanced printing technology was introduced as it became available, including Linotype machinery and halftone lithography. After 1890, the large newspaper sheet was abandoned for a smaller magazine format. Gray introduced innovative reporting techniques, and himself traveled to the Northern Pacific ceremony of driving the golden spike at Promontory Point, Utah. In the early years he wrote single-handedly nearly every department of the paper, and the increasing popularity of The Interior provided a direct measure of how the readership had taken to his fresh and invigorating style of writing.

The growing reputation of W. C. Gray was in part founded on a humorous view of the vain and officious pretensions of pompous clergymen. In the divided Presbyterian church of the late nineteenth century Gray good naturedly but unabashedly pointed out in print the fallacies as well as the strengths of both sides of an argument. Though he was not himself a cleric, high regard for his opinion in religious matters was widespread. His professional reputation as a newspaper man was also strong and his talent as an editor evoked a compliment from as far away as the London Times. Within a few years this esteem was formalized by the award of honorary doctorates from Wooster University and Knox College.

W. C. Gray residence #2 Charles C. Miller, architect Oak Park, Illinois 1890 |

Library |

Parlor |

Dining room |

After moving from Cincinnati in 1872, the Gray family settled in the suburb of Oak Park, Illinois, and two years later W. C. Gray employed Charles C. Miller to design the first of two residences that the architect would build for him. His wife established her own reputation as an artist by teaching drawing and hosting china painting parties. For frequent musical gatherings, she acquired a piano from a disbanded Oak Park social club. Itinerant artists were occasionally given room and board in exchange for a few days of instruction, and Catherine Gray used her developing talent to embellish her new house with paintings and stencil work.

The Gray family became respected members of the Oak Park community, although the writers, lecturers, social reformers and other progressives they entertained were sometimes suspect in the eyes of more conservative neighbors. By the late 1870s, their two children were old enough to marry. Son Frank S. Gray wed Alice Baker, and the couple had a son and two daughters before separating some years later. Anna C. Gray, the eighteen year old daughter of W. C. and Catherine Gray decided to marry a handsome commodities broker whose financial success was already apparent, Charles A. Purcell.

Charles Purcell (1854-1931) had originally come to Oak Park from the Purcell homestead in the Catskills in New York to attend school. In 1874, he went to work for his uncles at their trading post in North Bend, Nebraska, then four years later returned to Chicago to become a partner with his brother, W. H. Purcell, in a grain business. Their profitable partnership was incorporated in 1893 as W. H. Purcell Company, and sold in 1897 to the American Malting Company. Charles Purcell remained vice president and general manager of the company until his retirement from business in 1901. During his career Purcell became an arbiter of grain quality on the Chicago Board of Trade and eventually made himself a millionaire.

His marriage in 1879 to Anna Gray was socially

prominent, and Purcell was much liked by Dr. and Mrs. Gray. By the following

summer, the Purcells were expecting their first child. Wanting to ease the

delivery as much as possible, Charles moved his wife out of the inland heat to a

vacation cabin at Willamette, Illinois, on the shore of Lake Michigan. On July

2, 1880, their son William Gray Purcell was born, an

heir whose labors in life would carry forward the progressive example set by

William Cunningham Gray.