|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

2/9/2004

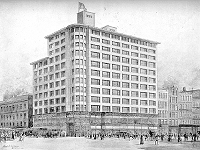

Presentation rendering

Schlesinger & Mayer Store

Louis Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie

Albert Fleury, renderer

Penny postcard, circa 1910s

Y'all come in, hear?

Lost pages happen. If I were two people, there would be more error checking on this site. Sometimes I find coding mistakes only when I happen to be looking at things for other purposes, as opposed to finding the errors introduced by external changes, vide below. Tonight I discovered that the nice group of images for the Schlesinger & Mayer Dry Goods Store were hidden behind one of those inevitable cut-and-paste repetitive mistakes that are largely invisible in the throes of working. So that's all repaired, but in the meantime all those pages were virtually lost.

To this very day, George Elmslie remains largely buried within the shadow of Louis Sullivan. Even though Larry Millett has conclusively documented Elmslie's authorship of the Owatonna bank in The Curve of the Arch, GGE seems stuck in most books as a designer of chairs and terra-cotta. Sadly, and against his own self-assessment, he is usually ensconced within Arts-&-Crafts treatises and exhibitions. The fact that he did almost all of the ornamentation of Sullivan's buildings, starting with Wainwright [St. Louis, Missouri] and Guaranty-Prudential [Buffalo, New York], is NEARLY everywhere overlooked. During his lifetime, he was always respectful and humble toward the honor of his master Sullivan. The letters he wrote to Frank Lloyd Wright defending Sullivan's memory are testimonies to his heartfelt loyalty. Still, modern scholarship ought to do better by the man.

2/8/2004

Charles R. Crane

1858-1939

Photograph by

Scot Zimmerman<-- A 1990s view of the second Bradley house, completed with vast "pushbutton" living as conceived in the 1910s. Mrs. Bradley said, "Well, it's a lovely house and we like it, but perhaps we did overdo the machinery a little bit. Sometimes it feels a bit like living in some kind of glorified office building."

Parabiographies entry

Gardener's cottage, Woods Hole. I never found it...what sweetheart details were sawed and glazed within, I wonder?Veni, vici, exeunt. Starting off with a re-read of that whole spiel, I went through the Minnesota 1900 essay and corrected a number of file conversion errors. A variety of revision approaches are tumbling around in my mind at the moment. Maybe I want to use the original text as a skeleton only, and write each section anew. In any event, the work of the moment is to complete the upgrade of the essay into a true hypertext document. Somewhere along the way I will break the whole thing down into more manageable segments.

A little discovery came my way via Yahoo! News this week: Turns out that scarcely five years after building the Josephine Crane Bradley summer residence for his daughter in Wood's Hole, Charles R. Crane was in Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution. Among the things he saw imminent was the potential destruction of the great bells of the Danilov monastery. He bought them, shipped them to America, and donated them to Harvard University. Crane was, of course, the most carte blanche client of P&E. Aside from houses, remodels, outbuildings, and numerous other works at the Juniper Point estate on Cape Cod, Crane paid for both the Josephine Crane Bradley residence #1 (by Sullivan and Elmslie) and Josephine Crane Bradley residence #2 houses in Madison, Wisconsin. Recounting his ambassadorial and philanthropic career remains for another time, but I remain amazed that the man is still making popular news some 65 years after exiting the world stage. Incidentally, I came across the repository of his son's papers at Georgetown University, where survives a small pocket of father-son correspondence (Box 1, Folder 5). Damn, how I wish I had been financially able to take up his granddaughter's invitation to stay at Juniper Point for a week (thanks to Gardiner)! I've been there (twice, I think, but I am not sure, the vagaries of my [thankfully] fading memory of the tragically tumultuous 1980s being what they are!), and the library tucked above the boathouse is a jewel beyond belief. Alas, I was there on a dark blustery day when all was shuttered. I could only glimpse into the darkness--no photography would serve.

2/2/2004

Surprise... Raw corrections. When circumstances part you from a long tended project, especially one in the ether realm, unpleasant discoveries can lurk unbidden at a moment's notice. The readership of this site tends to be research oriented; hardly a surprise. But imagine MY surprise when I discover, in spontaneously using my own site, that thousands of links have been rendered unusable by a coding change at the University of Minnesota Images servers. However, that has now been repaired and all those reference thumbnails once again open to the appropriate access and use page. Perhaps that is the largest update the site has ever had at one time: 186 pages (out of 1628)! I guess I have to stay more on top of things--a hint from the great beyond to get going on my affirmation expressed earlier (below). Actually, I did sketch out the next phase of development for this web sanctuary. The first step is to take apart the essay written for Minnesota 1900, break it down into section, and elevate the text into hyperthought. Imagine being able to footnote and illustrate without limit, relatively speaking. It's a whole new mindset, let me tell you. And I will, all in good time.

1/18/2004

Signs. As of August this year some 25 years will have passed since my entering into the stream of what Purcell referred to as the "Caravan." The poetic measure of that nomenclature carries a sense of the distant as well as the distance, things now passed into history and yet somehow still living in a train of being that WGP encompassed with the word "continuity." For whatever reason, I have struggled along. Early on I was given great advantages with grants and favors from men who knew or carried forward Purcell. His immediate family blessed me with generous gifts, from documents such as drawings, correspondence, books, and paintings, to generous repasts at elegant clubs. His last apprentice, Arthur Dyson, rendered for me the present day expression of the Message in a surpassing form, and carried me with him to the Taliesin Fellowship (for what that turned out to be worth). Clearly, I have been moved forward with some index of destiny, whatever my merits or lack thereof. But still I have not brought the camels home as I meant from the beginning.

All along, I questioned not my commitment to the task, but my worthiness. I am not an architect. I am merely a poet. And, in a kind of damnation, my prosody tends toward a democratic popularism, not the kind of stiff dry academic writing that pleases the cognoscenti of architectural historians. Perhaps I am not talented enough, I kept telling myself, not insightful enough in a technical capacity. Delay crept into intention, and here we are 25 years down the pike. I published 3 books and about 100 articles, some of which were translated into five languages, and still I did not have the feeling that I had done enough rightly to resolve the lingering sense of need that has drawn me forward all these years. I had written all that at the request of others, not to repose my own volition.

Today I attended the memorial service of a wealthy philanthropist who lived to be 88 years old. I sat in a historic Hollywood theater for whose restoration he paid and heard of his untiring signal support for major causes, including the creation of the Kennedy Center. Had he not acted, there would likely be no New York City Opera, and quite possibly no Joffrey Ballet. As I pondered the remarks of speaker after speaker, it came home to me in a profound way how very short life really is, regardless of the challenges of food and the rent. William Gray Purcell lived to be 85, and it wasn't enough for him, though his father was a millionaire when a million was more like a billion. I find from some well within that I must now turn my hand to completion of this task, whatever that turns out to yield in the end. I have other caravans yet to take, and this one must be brought to conclusion before those journeys can begin.

In a way, recently I asked for a sign about what I should do to accomplish this. Purcell and those other beings who remain potent--however that really expresses--have always been generous with such indicators, or at least things that served the purpose. I happened to have an offhand hour to spend and went into a Hollywood used bookstore. I walked to the first shelf, and reached out for something that looked familiar. It was a copy of the 1945 Knopf edition of Tertium Organum. Unlike all the other books around which I couldn't afford, this one was marked $8--the same amount in my wallet. It was the same version that Purcell had left in his library. Once I touched that book, my presence in the bookstore was no longer required.

Before that moment I was ready to give up, really, feeling that I had done all I could. I was into the belief that it didn't matter what more I had to say, that someone else could and would probably say it better. But that left me uneasy. So, I had turned within and asked, in my way, for some tangible sign of what I should do. The book told me. My job is not about writing what Purcell already wrote, or freeze-drying it into some academic tome. My job turned out to be--in that oh-so-satisfying-organic-way--what I am most perfectly suited to do. I shall write about the consciousness, not the number of nails or Roman bricks. And my uncertainty over the worthiness of publication? No need. There is this site. That's enough. What a relief. Perhaps no surprise to those in the distance with enough perspective to see me inching forward to that conclusion over these past years. That was the intellectual side, but this is the heart realization. Now I am free to bring it to my own closure, and that liberation means now, at long last, I have no further barriers to doing that bit of camel herding assigned for my stretch of the Caravan. We'll be seeing many things partly hidden by the shifting sands, but I should be able to stir the imagination to what is not overtly visible. And, as I remind myself above, have fun.