|

firm active: 1907-1921 minneapolis, minnesota :: chicago, illinois |

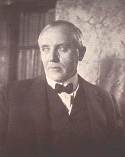

John Jager

1871-1959

Biographical essay in Guide to the William Gray Purcell Papers.

Copyright by Mark Hammons, 1985.

The man who served as the first conservator of the Purcell &

Elmslie archives was born in Vrhnika, Slovenia, and completed his secondary

education in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia. From 1892 to 1898 Jager studied in the

College of Architecture at the Vienna Polytechnicum, where he remained as a

university assistant for another two years following his graduation. During

these years he gained his first experiences in large scale planning under Karl

Mayreder, chief of the Vienna City Plan, and Max Fabiani, city planner for

Ljubljana after the earthquake of 1895.

Jager left his homeland in 1901 when he was appointed architect to the Austrian

mission to Peking. In China he designed and rebuilt the Austro Hungarian

legation building, which had been destroyed a year earlier during the Boxer

Rebellion. Jager was greatly impressed with Chinese culture and began a lifelong

study of the Chinese language and arts. Shortly afterward he also visited Japan

where he collected examples of vanishing handicrafts, particularly metalwork,

textiles, and wood block printing.

By 1902 Jager had relocated to the American Midwest where he was reunited with

his brothers who had earlier immigrated to Minneapolis, Minnesota. Jager

established his own architectural office. His commissions during the first year

included several Catholic churches for ethnic parishes, notably St. Bernard's,

located in a German neighborhood north of the state capitol, and another German

one, St. Stephen's in Brockway Township, Minnesota. In 1903 Jager published a

booklet titled Fundamental Ideas in Church Architecture that argued against the

rote use of historic forms in modern buildings. He also discovered he was among

the few architects in the state who advocated the use of reinforced concrete

construction, which many contractors at the time considered merely a passing

trend that was ill suited to the extreme variations of the northern climate.

Having established himself in his new country, Jager began a family life by

marrying a talented artist named Selma Erhovnic, whom he had met while a student

in Vienna. The couple settled on twenty acres in south Minneapolis near

Minnehaha Creek where Jager designed a large stone and wood house that blended

with the natural surroundings. Jager carefully landscaped the area with

plantings of red cedar trees, and he founded the Hiawatha Heights Improvement

Association that encouraged any new development to be similarly sensitive to the

wilderness beauty of the neighborhood.

Jager continued to develop a presence in public affairs that gained him a strong

local reputation. For the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exposition held at St.

Louis, Missouri, in 1904, he painted a large mural that formed the main exhibit

for Minneapolis and St. Paul. The painting provided a large scale aerial view of

the cities and surrounding communities, which were shown connected together by

the existing lines and proposed extensions of the street car system. Using his

experiences in city planning, he presented an integrated concept of development

for an area totaling two thousand square miles, which he subsequently promoted

in publications and public addresses. Jager became actively involved with the

Minneapolis City Planning Commission and was an author of the city plan of 1905.

Jager attended lectures by other speakers, and at a meeting of the Minneapolis

Architectural Club in 1908 he heard a talk by William Gray Purcell, which

prompted him to write a letter of introduction. In addition to sharing other

interests, Purcell and Jager found their approach to art and architecture had a

common basis in the organic principles espoused by Louis Sullivan. Jager

came to be regarded as "the silent partner" in the work of Purcell & Elmslie and

pseudononymously contributed an essay titled "What the Engineer Thinks" to the

the January 1915 issue of the Western Architect that illustrated the work of the

firm. Over the following half century the acquaintance between the Jager and

Purcell ripened into a friendship in which both found comfort in times of

personal adversity.

In 1909 Jager began working for the prosperous Minneapolis firm of Hewitt &

Brown, where he remained for the rest of his professional career. There he

specialized in engineering that used new materials and served as librarian and

archivist for firm's records. Among his contributions to the work of Hewitt &

Brown was the design of the interior ornament of St. Mark's Episcopal Church,

built in Minneapolis in 1908 1911. For a time after World War I, Jager returned

to Yugoslavia with a unit of the American Red Cross to rehabilitate small

villages that had been devastated by fighting in the Balkan countryside. His

efforts were eventually recognized by an award from the Yugoslav government.

By the time Jager returned to Minnesota, his friend Purcell had moved to

Portland, Oregon. The two men continued to share their thoughts in frequent

letters, and Purcell occasionally visited Minneapolis to pursue architectural

commissions. On one visit in 1928, Purcell stayed at the Jager summer cabin on

Lake Vermilion in northern Minnesota, an experience that was intended to

refresh his spirits after an extended bout of business misfortunes, including

several failed projects for houses in Rochester, Minnesota. The retreat at Lake

Vermilion, during which Purcell appeared to be quite ill, was the last time the

men saw each other, although their relationship continued in a prolific

correspondence for the rest of their lives.

The stock market crash of 1929 resulted in financial ruin for Jager, who

retained his house in Minneapolis and the Lake Vermilion cabin through the

generosity of Purcell, and his longtime employment at Hewitt & Brown ended

abruptly when that firm fell victim to the Depression. From 1933 until his

professional retirement, Jager worked on several projects as superintendent of

federal works for the Works Progress Administration, where he worked with former

Purcell & Elmslie drafter Frederick A. Strauel. By 1940 Jager was also an

editorial associate of Northwest Architect, the monthly journal of the Minnesota

Society of Architects. He suggested that Purcell, then living in southern

California, make a contribution to the magazine. Thus began the fifteen year

series of articles by Purcell that appeared in Northwest Architect, a production

in which Jager was constantly involved.

In the last decades of his life Jager was intensely devoted to his scholarly

studies, particularly archeology. Although he published little, he did extensive

research on the undeciphered Etruscan language and other ancient cultures. He

collected a large library on art and architecture and systematically cross

referenced the collection to his own copious notes. His correspondence with

Purcell was the principal means of reporting his discoveries, his letters often

running to many pages in a thin, fine hand. In turn, Purcell addressed

innumerable short notes to Jager to share his own reading and thoughts on

contemporary events.

One Jager's major accomplishments during his later years was the conserving of

the records of Purcell & Elmslie and other archival materials that came into his

possession. Perhaps even more than Purcell, Jager understood the historical

significance of the materials that had been stored in his basement work rooms

since the 1930s following the close of the last office space kept by Purcell in

Minnesota. During the following thirty years he spent countless hours

identifying, cataloging, preserving, and studying not only the architectural

records but also the many other documents that Purcell continued to send to him.

For example, Jager assembled the records of the Gray family into chronological

order and, assisted by Frederick A. Strauel, he prepared the numerous display

panels for the exhibition of Purcell & Elmslie work held at the Walker Art

Center in Minneapolis in 1953.

In the last years of his life Jager was physically handicapped with chronic

illness and became somewhat antagonistic over what he perceived as a lack of

appreciation for his endeavors. The death of his only child during the 1940s

greatly saddened him, and his marriage to Selma Jager grew progressively

cold. He began to spend long periods of time alone at Lake Vermilion, isolated

and brooding over the course of his life. His letters to Purcell eventually

became openly hostile toward his friend as he expressed his disappointment at

the work he had done and a resentment that recognition was apparently going to

those who merely harvested his labors.

Unfortunately, the full extent of Jager's accomplishments as a scholar will

never be known. While his mark on the Purcell & Elmslie archives and other

Purcell records preserved many thoughtful comments on art and architecture, most

of his own notes and research materials were ordered to be burned by his widow

after her own death in 1974. An estate sale liquidated the library that he had

so carefully assembled and dispersed his art collections. Although some Jager

papers were indicated to have been sent to an archive in Ljubljana, the efforts

given by John Jager to the preservation of the Purcell Papers remains his

lasting contribution to the endurance of the organic principles in which he

believed.