|

|

|

Purcell and Elmslie, Architects Firm active :: 1907-1921

Minneapolis, Minnesota :: Chicago,

Illinois |

Ye Older Grindstones

5/2/2006

Fuzzy and indistinct

George Feick, Jr.

1906

Photograph by William Gray PurcellBetween Two Georges. Over the years I have on occasion felt strongly the psychic company of both William Gray Purcell and George Grant Elmslie, not always steady yet truly palpable at times (whatever that means). It is a true story that once I seemed to have even channeled a caricature sketch by Elmslie of himself, complete with the scrawled caption "Eat me with a fine tined fork," which is of considerable interest to me only because I have no drawing skill whatever and I had yet to even read a single one of his letters when that happened. I had no recollection of actually doodling, but just looked down and there it was on green slip of paper. Say what you will. Only in fleeting twitches, however, have I ever sensed anything like personal presence from George Feick, Jr.

Strange as it seems, and this is Purcell's own perception about his wife and life in general as well, we owe the existence of Purcell & Elmslie to George Feick. It was Feick who talked Purcell into moving to Minneapolis and opening shop. Yet partner Feick is something of a vacancy, even though his name is on the sleeve of two of the three Purcell partnerships that get conflated in general usage as Purcell & Elmslie. There was not technically speaking an Elmslie on the tagline from 1907 to 1909, but in real effect he was there - something always acknowledged. Purcell recounts in his attempt to design his own first house in Minneapolis the inexorable need to consult Elmslie, who always served as a friend, correspondent and colleague, in order to get any traction on a viable design. From the beginning to some degree it was always Purcell, Feick, and Elmslie.

There is a draft typescript from the Parabiographies manuscripts, much stricken by hand on later review, where Purcell recounts his causal meeting with Elmslie and goes on to invoke the pros (few) and cons (more space taken on the page) of George Feick. These remarks contain information hinted at in only one other place, a letter of office recollections supplied to Purcell and also written in the 1930s, by former P&E secretary Gertrude Phillips. The other few comments and notations that survive elsewhere are, seems to me, more perfunctory explanations made visibly out of practical necessity or gentlemanly form.

This fragmentary manuscript is very important in understanding the genesis of P&E. We learn that Purcell did not really want to go to Minneapolis, but preferred Los Angeles. This no doubt stemmed from his early effort in 1904 to get work with Myron Hunt, and the natural social connections he would have automatically enjoyed with the presence in the city of his father's sister, Mrs. W. H. Purcell, for whose residence he would later do an "alterations project" that was most likely a potential pretext for visiting southern California. Of course, Purcell wound up there anyway, in 1930 at the sanatorium in Banning, near Palm Springs and then removed to Pasadena/Monrovia where he remained immovably for the rest of his life on his own little plot of well-gardened heaven at "Westwinds." However, by 1906 when he and Feick went to Europe Purcell had already been infected with tuberculosis from his time working in Seattle at the A. Warren Gould office, so that critical path wouldn't have changed had he chosen palm trees over Minnesotan permafrost.

Still, the last paragraphs are a remarkable summary by Purcell of what came from his reluctant decision - and he doesn't really explain what tipped the scales - to open an office with Feick in Minneapolis. The whole ball of wax hung in the balance, as he notes:

"If I had chosen Los Angeles, I'd have missed the continuity of life contact with George Elmslie, and would have never met John Jager, the two forces which, with Grandfather Gray, made me what I am. And I'd have missed marriage with E.S.P. [Edna Summy Purcell; and Lake Place!].

Impossible to imagine what sort of man and mind I'd have come to be. A more peaceful - perhaps - but much less exciting life, and I feel certain I'd have never made the mark in Architecture that was accomplished by us as a team." (1)

Office Building for George Feick, Sr.

Purcell and Feick, Architects

Sandusky, Ohio 1908

George Feick, Jr., was just the price that Purcell paid.

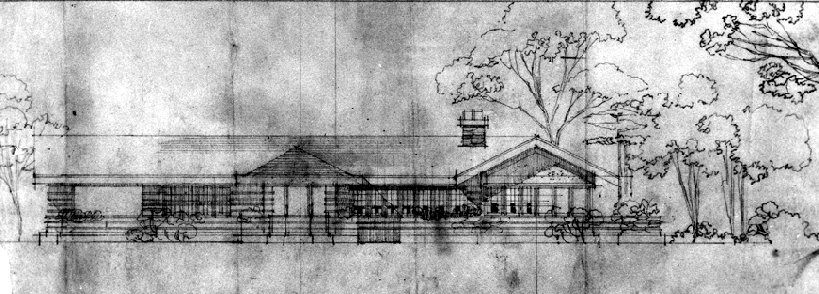

Presentation sketch

Harry D. Page residence, project

Purcell, Feick and Elmslie

Mason City, Iowa 1912Other notes: In the "learn something new every day" department, I was re-reading H. Allen Brooks the other day and saw mention that P&E prepared a plan for the Page residence in Mason City, a house which the Griffins wound up doing. How had this eluded me all these years? Surely it must have been on a need to know basis! I guess I need to know, now, so I took a peek at the drawing above and saw what a completely different feel the P&E version was from what Page decided to build. I have also put up the framework to mount a very important manuscript by Purcell, one which is in effect his autobiography. Since there are 175 pages of typing facing me to get this up, it's going to be a background project with a chapter a week as my goal. The photocopy I have is decades old and while I made scans and tried PDFs, they are very difficult to read. Plus, as always, typing will allow hyperlinks throughout the rest of the P&E pages..

Next up: The vocabulary of enrichment.

4/25/2006

Web Ring Around the Poem.

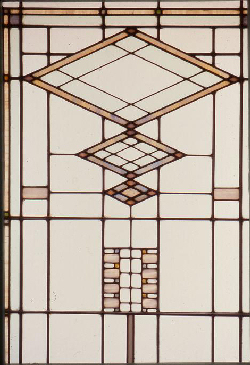

As noted in a recent Grind,

when people engage

with the internal architecture of forms in Prairie designs they almost always do

so through decorative elements. These are the doorway to the senses by which the

inner skeleton, as it were, of the structure can be made to rise to

consciousness. One particularly inevitable impression comes through leaded

glass, since the patterns are wholly integrated with the function of admitting

light not only to the house, say, but also to the eye. At least during the

daytime, the medium cannot escape being the message.

Much is made in these pages of the need to examine

the fourth dimension as a stream of awareness behind the work of the

Progressives. A very focused, very thorough, and very finely detailed dissection

of this conversation in terms of European progressive artists, particularly

Kandinsky, was published by Linda Dalrymple Henderson in her book The Fourth

Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art (Princeton University

Press, 1983). The book includes a strong look at the American side of the pond.

To reflect the rarity of this understanding in the broader public even today, if

you can find copies the paperback goes for about $200 and the hardback usually

has a price tag of $300, though sometimes they come up on Amazon a little

cheaper. The only reason I was able to read this book was the tip from Dick

Kronick that it existed and my much valued access to the Getty Research

Institute.

Although the Henderson book is superb and

essential, saying "open sesame" to P. D. Ouspensky's Tertium Organum is

easier and more straightforward. Therein the goodly seeker will find the nature

of consciousness explained as a relationship of movement to three dimensional

space, something akin to what

Edwin A. Abbott was trying

to do in Flatland : A Romance of Many Dimensions only in a more

mathematical format as he pointed out the differences between one and two and

then three dimensions. Of course, everyone in the market at the time was trying

to point out by inference the characteristics of a fourth one, which we

can not see from the containment of our physical senses in the third.

One way the P&E made a pun and a

point was to create decorative patterns for the planar surfaces of walls that

were expressions of three dimensional forms like -- dare I point out the

obvious -- corners. I will leave the above illustrations to speak for

themselves, with the one caveat being the only good corner shot I had happened

to be of Wright's Unity Temple, but that is not to be taken in any way as an

attribution to him of the idea. It is, however, a nice touch that the

corner in question anchors a church.

Enlightening moments have their own raison

d'etrere, and the rest is commentary. Buddha is said to have mentioned this when

he attained enlightenment by immediately stating, "This cannot be taught." He

then went on to a ripe old age answering questions, fortunately, "so we are

told," from a basis of omniscience. The received wisdom in quotes preceding was

delivered from Mount Sinai upon one of my writings by a former editor and

represents one of my own small passages of realization. Although what I got was,

ironically, not the intended literary scorn, the phrase marks a watershed in my

education about the distinction between the static descriptive field that is art

history and dynamic poetry that is the nature of understanding artworks. Until

the jiff of tutelage, I had labored under the collapsed notion that the

same words could serve both functions simultaneously; perhaps at best

passionately in love or at least conceived as a marriage of convenience with

prospect of romance to come.

The understanding and the describing of artworks

seem to be, so I tell myself, separate, apparently mutually exclusive functions.

Books on art many times present exquisitely detailed compilations of facts,

often including precise measurements of time and space that crisply define the

material substance, form, punctuation, and passage of individual objects, the

whole strung together like a pearl necklace placed carefully in a satin-lined

velvet box shut with a golden clasp. These productions can be perfect

narratives, veritable Swiss train schedules. You can set your gallery watch by

them and never miss a connection. Such works serve a practical, essential

purpose, yet as well as they lead to horticulture they cannot make you think

like a walk through the wilderness does. Art history is always "so we are

told."

Beating a dead horse is, dare I venture to say,

ironic.

The experience of irony, for example, is an

altogether different matter than the description of it. Fowler's Modern

English Usage (1926) has this to say:

"Irony is a form of utterance that postulates a

double audience, consisting of one party that hearing shall hear and shall not

understand, and another party that, when more is meant than meets the ear, is

aware, both of that more and of the outsider'sincomprehension."

Buying into art history, akin to much of what

passes for "fine" artwork these days, is very like any concern over the expense

of owning a yacht. If you have to ask what it means, then you don't understand.

Purcell and Elmslie both commented on the emergence of what gets called

modern art, say from the end of World War II forward. Art, their one-time

willing ally in architecture, disconnected visibly from relevance in

symbolically shared life to totter amid intellectual fields of personal

self-absorption upon which many art histories have, ironically, been erected.

WGP and GGE were flabbergasted with a Perfect Storm combination of horror and

helpfulness that can best be summed up by asking "You don't really mean

that, do you? You poor thing."

All of which brings me to the ultimate point of

this Grind: to express my profound appreciation for those who seek out the

experience of the object, rather than dwell in the shadows of the description. A

number of these individuals have made contributions to this web site, and in

addition have raised up their own as a means of sharing in larger community. I

encourage your visits to these sites, presented here mostly in the chronological

order of their acquaintance to me:

While Purcell would have gently chided Tim on the

choice of name, since the Prairie school architects regarded the notion of

style, per se, as their philosophical enemy, the content and presentation on

this site reflect a genuine happy spirit of engagement. Tim has graciously

permitted some of his images to appear on Organica, and I have learned worthy

things from his pages that I did not know. This is fine place for the general

explorer to commence study.

The subtitle for this exquisitely useful site is

A Gazetteer of Extant Buildings. The marvel of the idea is that we need

to know what remains and where we can find it. The author is fortunate in being

able to travel and has exercised his deep interest in the Prairie School

according to opportunity. In the gift of his site we can share the trail of

discovery and make ready our own expeditions. John has also contributed images

to Organica, as well, including P&E buildings I've never made it to see, so my

gratitude is abundant. Phil Pecord, a fine gentleman with whom I corresponded a

few years ago, has permitted John to add his extraordinary compilation of

Prairie School building information to The Prairie School Traveler; integration

is ongoing. If you're going to see the sites of the Holy Land, this is the

portal to make your itinerary.

While I know that Mike Springer plans a

self-publication of his interest in Prairie School along the Kansas/Missouri

axis, perhaps he can be persuaded to put up a web site. With great generosity,

Mike pursued research relating to John Jager for me, and has continued to

correspond with additional information about Sullivan and Elmslie. Dick Kronick,

a committed member of the Caravan, has supplied some images and promises more.

There are others who seek anonymity but who have also added the treasures of

their quest to Organica, and I want to thank them here, again, in public, if

without attribution. Everyone, come on, get on board the soul train. Next up: George

Feick, Jr., with red panang curry sauce.

In a

moment of a thousand words

The nature of the corner flattened into a plane

Unity Temple

Frank Lloyd Wright, architect

Oak Park Illinois 1906

This fourth dimensional message

Leaded glass pattern

Edna S. Purcell residence [Lake Place]

Minneapolis, Minnesota 1913

Sawed wood bracket

John Adair residence

Owatonna, Minnesota

A brief digression...

After the divorce,

alimony was eventually awarded in the form of programs that required

the token purchase of "artwork" based on a tiny percentage of overall

construction cost. This was especially true of public buildings, but

also of corporate towers, which an insightful wag nailed perfectly,

sotto voce, as the "turd in the plaza" school. Although some like

Frank Lloyd Wright never pretended to be in one, most architects have

come out of the closet now, somewhat passive-aggressively posing as

virtual Buddhas to inform us of what cannot be taught, but may be

rendered with dizzying formless sketches and elaborate computer

software. Architects and artists still belong to the same club, they

just don't speak to each other anymore. I'm sure it has to do with who

is getting what percentage of money.

PrairieStyles,

presented by Tim Loftus

The Prairie

School Traveler, presented by John Panning